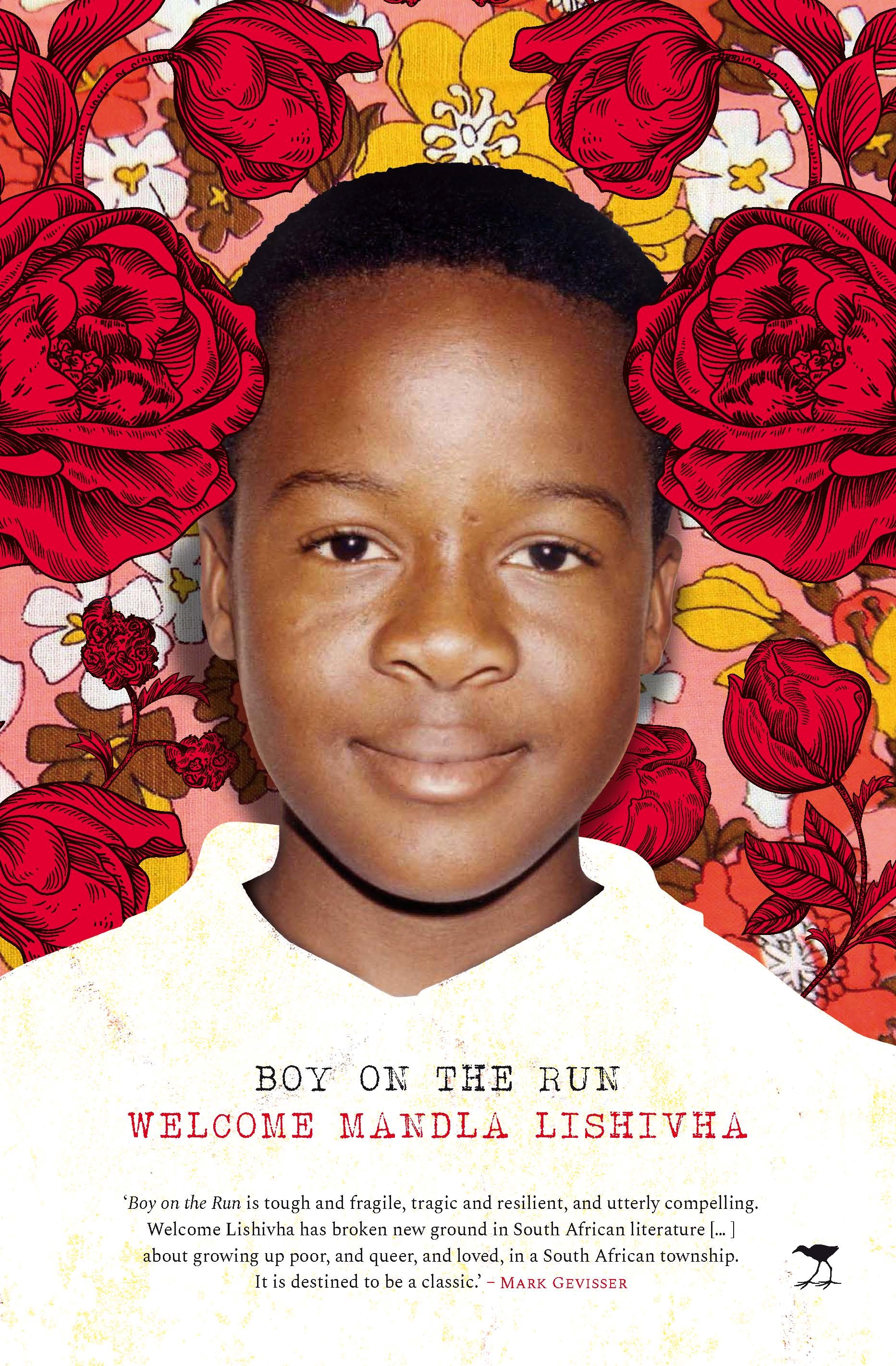

Growing up poor and queer, and loved, in a South African township. The memoir Boy on the Run by Welcome Mandla Lishivha is “destined to be a classic”, says acclaimed South African author Mark Gevisser. ‘It’s tough and fragile, tragic and resilient, and utterly compelling. Welcome Lishivha has broken new ground in South African literature.’

South Africa’s cultural wires are abuzz about Lishivha’s debut. Readers have found themselves moved by lyrical lines like: ‘It is the godly feeling of dancing like a goddess and snapping on a beat with sheer joy that makes all the trouble life demands worthwhile. In these moments, of intensive freedom from pain, of joy that knows no bound and peace that passeth all understanding, I become that kid again, dancing with my mother.’

Welcome Mandla Lishivha’s exquisitely crafted memoir is unlike anything you’ve ever read. Boy on the Run is a staggeringly beautiful and honest exploration of identity through grief, love and friendship, giving us, the readers, a glorious song of self-expression.

Here’s an extract!

---

People were milling about on the main road just outside ko Matlapeng as we got off the second taxi from Mabopane station. Music blasted from the carwash nearby and taxis hooted as they dropped off and picked up people who had gone shopping in town or Mabopane station.

Mama and I walked in through the glass sliding door and waited our turn. I paged through an old copy of Drum that was lying on a spread of magazines on the coffee table.

The man who did my s-curl and cut was tall, skinny and had an elaborate curly cut himself. He had a few people to get through before us, but Mama said we’d wait. First he reduced the sides on my head to a brush cut, leaving ample hair on the top. After removing the split ends he applied the Sofn’free relaxer, combed through my hair and said to tell him when it started burning. When he washed off the relaxer, I had a curly perm on my crown with the brush hair on the sides soft, shinier and flat. He ran his palms over my curls with Special Feeling gel and sprayed my head with sheen. Mama went for the s-curl with a side-cut. Instead of keeping her crown upright, he styled it skewed to the side like my dad skewed his beret to the side when he was wearing his army uniform the last time I saw him. She got up with a curlier, shinier and blacker side-cut.

When we walked out ko Matlapeng, adorned with glistening halos from our shining curls and both in our denim, we were ready to take over the world. We stood outside the salon in the distracted street and inspected each other’s hair in sunshine so bright we used our hands to cap the sun. We were relieved to leave the packed salon and were appreciative of each other’s transformations. We walked down the street hand in hand. We stopped to buy food at a stall with white plastic chairs and a metal folding table beneath a red Coca-Cola sign.

Mama ordered one large plate with fried chicken, pap, chakalaka on the side, a generous amount of gravy, fried cabbage and a two-litre Coke to wash it down. We sat across the table from each other. While our food was being prepared Mama asked for a bowl of warm water to wash our hands. When it arrived her plump, warm hands gently took mine, clasping them and immersing them in the bowl of water between us. She scooped up some water in her cupped palms and poured it over my hands, opening my palms to rub them softly. She scooped up more water and began on the backs of my hands, using her middle finger to rub in between my fingers. They looked so tiny next to hers with the red painted nails. She clasped both my hands again with her warm embrace and sank our hands in the water, which illuminated our skin and seemed to magnify our hands. The illuminated colour on our skin, immersed in the water, with the aroma of fried chicken and fried cabbage swirling around – she made everything so perfect.

‘I found a room to rent ko di K and was wondering if o nyaka go tla le nna.’ She paused and looked up as if waking up from a trance. ‘I mean, if you are happy go nna le Koko, that’s also fine,’ she said, ‘you know, because o nale di chomi. Mara I am just saying, you can come to stay with me ko di K, if you want. Aus Julie has three sisters, and they have children that you could also make friends with.’ She grabbed the blue and white scotch towel and started drying my hands. ‘Ke nyaka go tla l’ wena,’ I replied as I surrendered my hands in hers, hoping she understood how badly I never ever wanted to leave her side. Even if it meant leaving all my other darlings behind.

Welcome Mandla Lishivha (1991) is a freelance journalist and PhD candidate in Jurisprudence at the University of Pretoria. He has a Master of Arts in Journalism and Media Studies, a Bachelor of Arts with Honours in Anthropology and a Bachelor of Arts in Media Studies & Anthropology. He has written for the Journal of Contemporary African Studies, Daily Maverick, Mail & Guardian, Reuters, GQ and City Press.

Purchase a copy of Boy on the Run here.