While institutions continue to drag their feet over returning looted heritage to Africa, Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs) are bringing art home, one digital scan at a time.

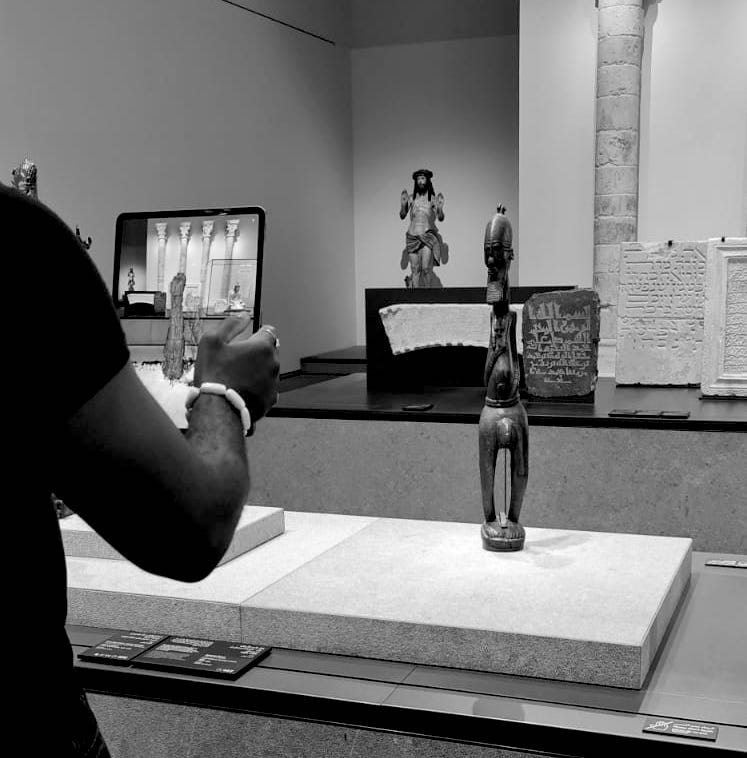

Standing in front of the Benin bronzes in the British Museum room, Chidi Nwaubani uses a LIDAR scanner to scan the artefacts one by one. The scanner is an advanced scanning technology used to generate high resolution three-dimensional digital models, but Chidi is neither an archaeologist nor a restorer from the museum. Instead, the Nigerian digital artist is collecting data for his project Looty, a series of 3D images of stolen African artworks that he makes into NFTs (non-fungible tokens). An NFT is a certificate of authenticity written into the blockchain, which is associated with a physical or virtual asset (here, a digital artwork). By transforming “ancient looted art into digital art tokens”, Chidi aims to free such artworks from their captivity- at least virtually. Nigeria has campaigned for years for the return of the precious cultural artefacts themselves, but the British institution continues to refuse to return them.

Isn’t creating and selling digital doubles counterfeiting? Nothing says the activity is illegal, underlines the artist with a smile. "No text of the British Museum forbids to make this kind of copies". Welcome to the magical world of NFTs, where the lack of legal barriers leaves the field open for artists to experiment with the potentials of the new medium, and to imagine new solutions o reclaim their heritage. "It's a game-changing tool" says the artist who is also planning to produce NFTs for a future “first virtual museum for Africa”, a self-funded project designed by a Rwandese Art collective located in Kigali.

Welcome to the magical world of NFTs

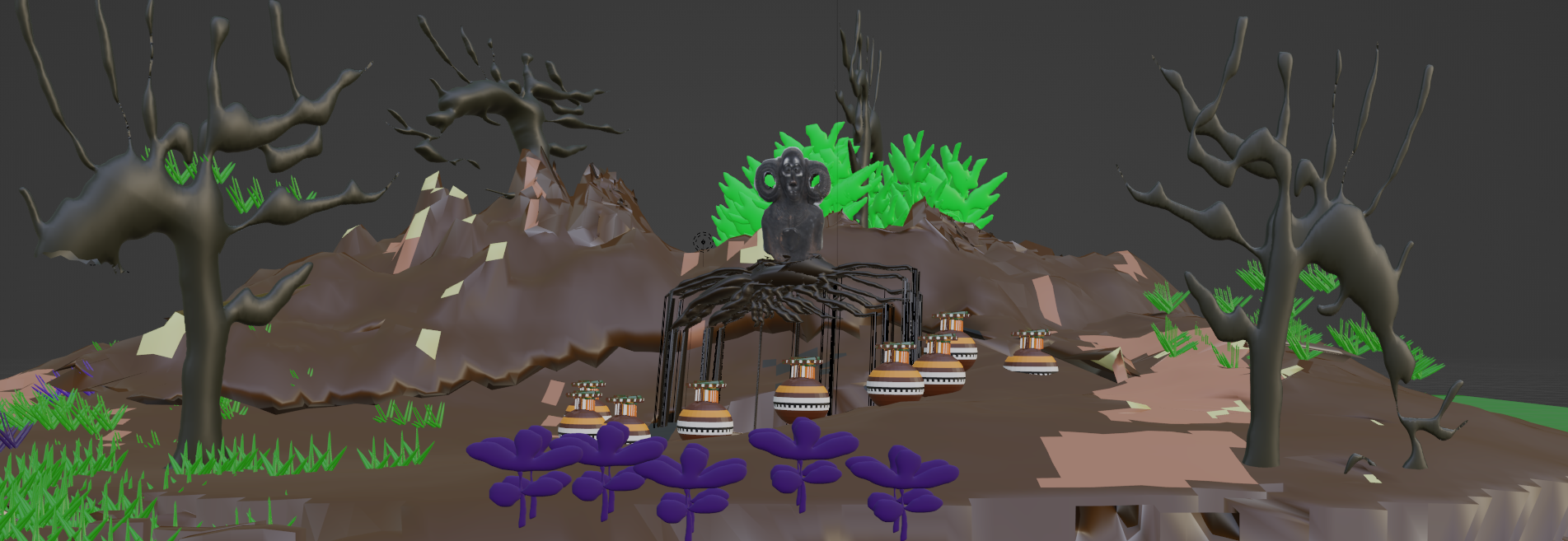

The digital institution, named Milele, will be dedicated to “African artefacts that have been stolen during colonial and post-colonial past, explains artist and cofounder Melissa Kurkut. “Many African countries have been asking the Western world to return their artefacts, but some of them have stated laws saying that art collections belong to the states, so our project is an “in between” solution to remove these barriers and give people access to these artefacts, while we are waiting for the physical repatriation”. The museum – “where each artwork will be displayed almost the same way they were displayed before they got stolen: a village, a city or a worshipping place” as cofounder and artist Bruce Niyonkuru explains – will open its virtual doors next summer.

NFTs to buy back land

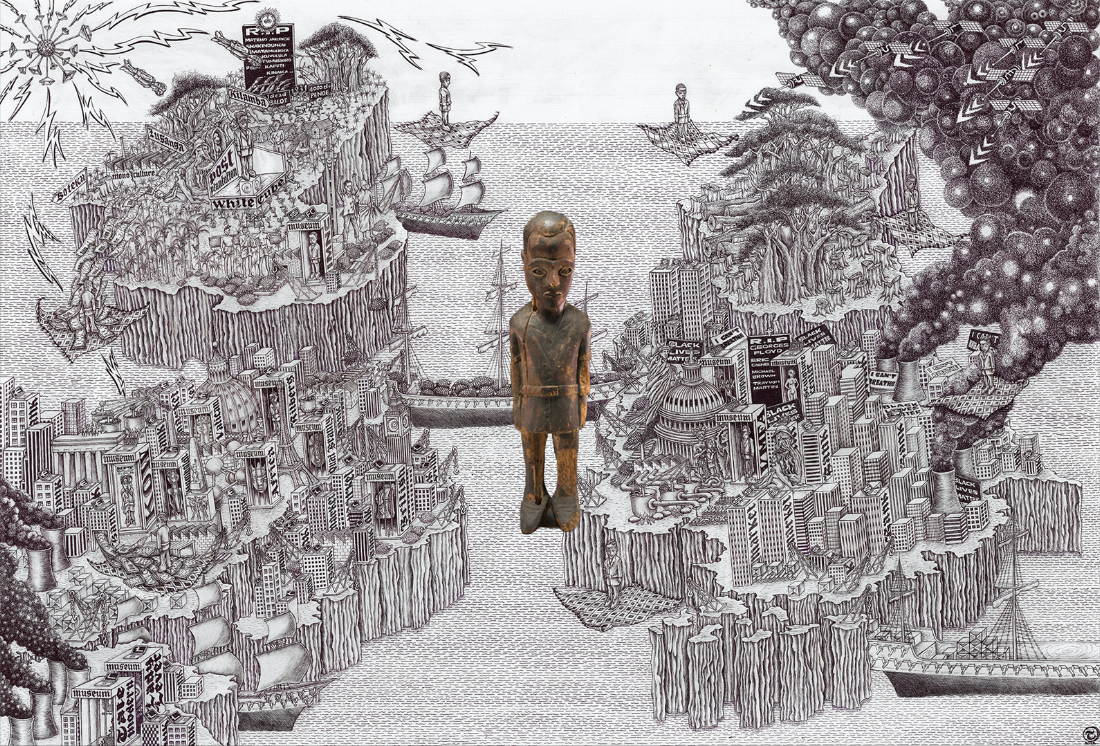

In the parallel world of the metaverse, resistance is being organised. Congolese Plantation Workers Art League (CATPC), a Congolese art collective, has arranged its own “digital restitution” of Balot, a wooden sculpture kept in the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond that was carved in 1931 in their native plantations, in Lusanga. Depicting Maximilien Balot, a Belgian colonial agent killed during a rebellion against atrocities conducted by Unilever’s representatives, “the sculpture was created in order to contain his angry spirit”, explains Ced’art Tamasala, a member of the collective, ”to make sure that he would no longer harm the workers of the plantation; it is more than an object for us, the sculpture allows us to resist to the oppressor”.

But when the collective asked for a loan to the museum “to be able to show the sculpture in our art space at the plantation and make people reconnect with their own story, their heritage, they never agreed, despite our numerous letters". Refusing to stop their journey, they made more than 300 NFTs of the sacred statue of Balot. Each token corresponds to one hectare of the land destroyed by monocultures in Lusanga that the collective will buy back and restore. “The NFT technology seemed to us the best way to get closer to this sculpture, and benefit from its spiritual force, and heal our community and our land".

But could NFTs also be used as a tool to decolonize the art world? “It gives us access to a world that is traditionally elitist, it opens its doors to new entrants”, considers Chidi Nawaubani. According to Laurence Allard, a French specialist in digital uses and science communication based at Lille University, NFTs are a vector of inclusiveness for Africa, and they also benefit from the continent’s experience with cryptocurrencies. “With its low level of banking, Africa has been experimenting for several years with new technologies and searching for solutions to resolve the issue of money transfers, and NFTs are grafted onto this technophilia found in pioneering countries such as the Central African Republic or Nigeria, she says. While the subject is very divisive in Europe for instance, there is less judgment, less taboos than in France for example”.

Environmental impact

The multiplication of spaces dedicated to NFTs in major art events such as ArtXLagos, Art Basel, or at the Venice Biennale this year, are testimony to the fact that NFTs are now part of the African contemporary art scene, thinks Victoria Mann, the founder of AKAA (Also Known As Africa), a contemporary art and design fair in France centred around Africa, who is hosting her first NFT project this year: “The medium has grown so much that it has become unmissable”. Still, the market needs to adapt to this technology which is revolutionising norms. “For us, the challenge is to think about how to expose them, how to value these non-tangible works of art in the real world, and that’s not easy", explains Mann. The medium also has a kind of frontier feel to it, since it is not currently linked to strict regulations.

The medium has grown so much that it has become unmissable

In the case of the CATPC, the Guardian reports that the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts has protested the violation of copyright that the photographs of the work represent. Moreover, the environmental impact of NFTs could put the brakes on the craze for this new medium of expression. "There are clearly artists who refuse to experiment with NFTs because of their environmental issues”, explains Laurence Allard, pointing out the ecological cost of a single Ethereum transaction (a common digital currency used in NFT transactions). “When we think about it, our smartphones, computers that allows us to produce digital art, are also contributing to destroy our land and our people who are working in the cobalt mines”, responds Cedart, but if we don’t use them, others will do it, for harmful purposes. So at least, what we can do is to embrace it and do something good for our land and our community”.

Aimie Eliot is an independent journalist currently based in Japan, covering cultural, environmental and social topics. She previously worked in Germany and Eastern Africa (Ethiopia and Uganda) as a correspondent for French and German medias.