This year marks my fourth time serving as a member of the panel judging the annual Contemporary African Photography (CAP) Prize. Every year it offers my fellow jurors and I a unique opportunity to engage with a dazzling array of photography from and about the continent, spanning all styles and disciplines. But the judging structure is designed in such a way - we submit our ratings privately and they are totalled up - that even the judges do not know the final winners until they are announced. This makes the announcement of the overall winners an exciting moment. I get to see some of the projects that I had voted for making the final cut, and I take a fresh look at projects that resonated with other judges.

There are very few African photographers, and particularly women, in positions of prominence in the world of photography, and this matters. What we see informs what we know, and different people make different pictures, which in turn differently shape their audiences’ experiences of topics and narratives. This year the CAP Prize marks a milestone reflective of the wider renaissance in African photography. The majority of this year’s winners are women, and every one of the awarded photographic series was made by a photographer who not only works on the continent but was also born there.

The CAP Prize has always played a role in diversifying narratives and engaging actively with the continent and its practitioners, but it’s hard to get around the fact that much of the contemporary photography about Africa is made by non-Africans. So it comes as a great delight to me to see this year’s list of winners representing the continent so clearly. They are young, they are creative, the stories and strategies they bring us are fresh and exciting, and they reflect the best of contemporary African photography.

So who are the winners of CAP Prize 2022, and what is their work about?

Memory and Identity

A young Egyptian visual artist, Amina Kadous explores concepts of memory and identity and often takes her family history as her departure point. In White Gold (2021) Kadous travels back to El Mehalla Al Kobra, home to her and her family and the famous Egyptian cotton. She believes in the ephemerality of experience and therefore she sees herself and her family history reflected in cotton's journey. For her, a photograph is an object which holds meaning and memories and by drawing on the legacies of her grandparents, their archives, and her own country’s eroding history, she reflects on, and reconnects what is left of what once was a major symbol for Egyptian identity and cultural wealth as well as her own family’s place in it. With her work she makes connections between the past and present through layers of time as they fold and unfold.

Breaking social and political taboos

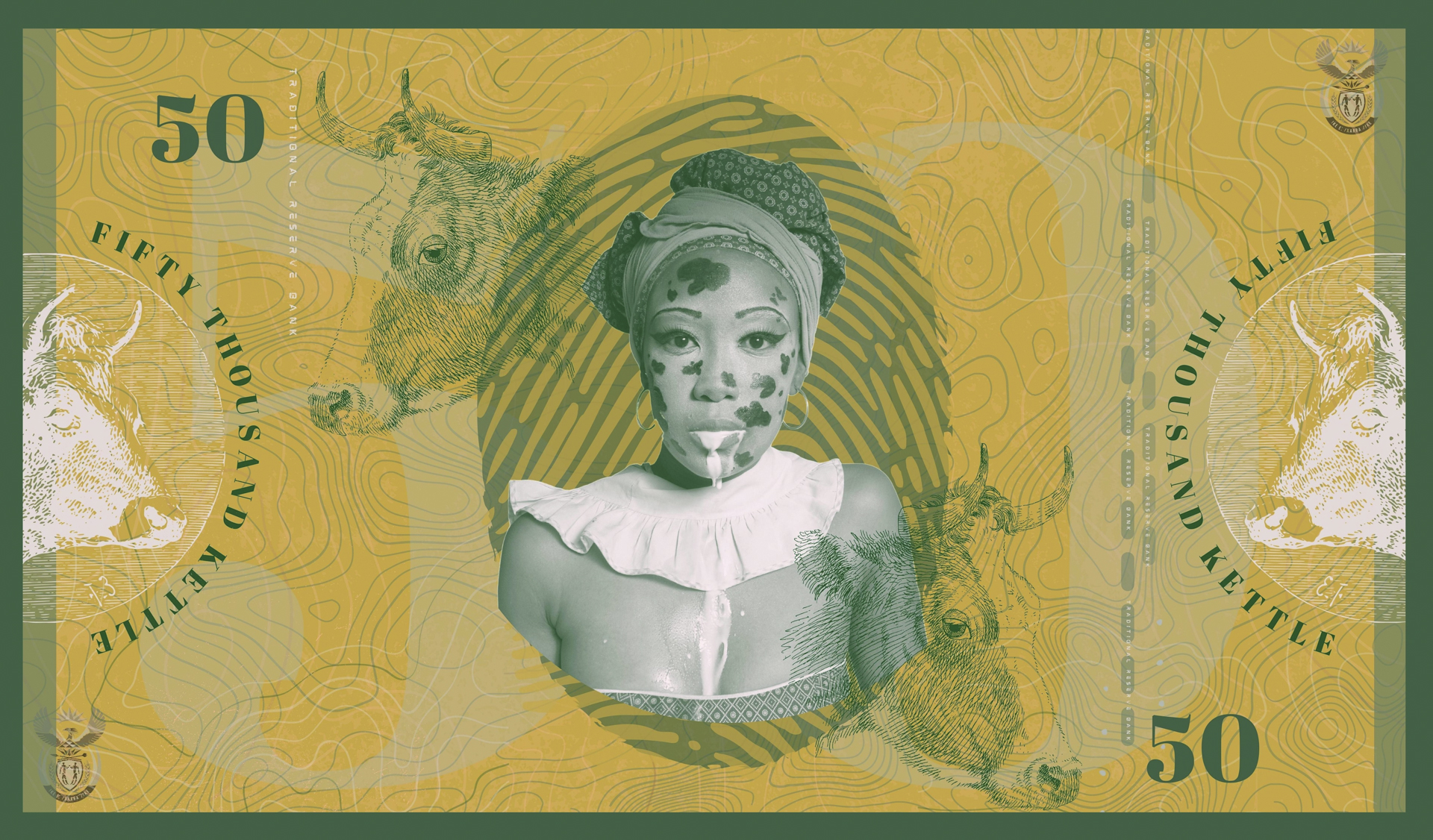

Remofiloe Nomandla Mayisela is a lens-based artist from Johannesburg whose imagery stems from her own experience of breaking out of widely-held social norms and taboos. Primarily through self-portraiture Mayisela’s imagery explores aspects of women's lives. In her series Lip Service (2022) she takes a closer look at the notion behind a popular idiom, ‘the way to a man's heart is through his stomach’. It’s a saying that is still common despite the supposed emancipation of women. Through her experience as a young modern-day makoti (a South African term describing a bride or a daughter-in-law), she began to question the strong cultural and patriarchal norms that assign women to kitchens and designate their bodies for consumption. In her images she combines strange performative elements and through the clothing she wears she signals that these realities are not limited to nationality or geography.

Eggs, from Lip Service series (2021) © Remofiloe Nomandla Mayisela/CAP Prize 2022

Feminist dreaming

Also from South Africa, Lee-Ann Olwage looks at the importance of education, especially for girls. For this project she worked with girls from Kakenya's Dream, a non-profit organisation based in Kenya that uses education to empower girls and end harmful traditional practices including female genital mutilation (FGM) and child marriage. Olwage, a visual storyteller whose practice predominantly focuses on identity, collaboration, and celebration, aims to create a space where the people she collaborates with can play an active part in the creation of images they feel tell their stories in a way that is affirming and celebratory. What happens when a supportive environment is created where girls are given the opportunity to dream and thrive?

Breaking the cycle

Double identité (2019) by Pamela Tulizo also addresses women’s positions in African society. Tulizo realised her project in her hometown of Goma, the capital of North Kivu province in DR Congo. She was disturbed by the local press’ insistence on portraying women in the role of victim. Her images, on the other hand, focus on how those same women would like to be represented - as proud, beautiful women, strong and full of energy and ready to fight against social injustices. Their dual identities are constructed with the help of actors, mannequins, and dancers. Tulizo disagrees with the dominant reporting and representation of Goma and the DRC by many international press, NGOs, researchers, and artists, all of whom she says perpetuate old narratives and cliches. She claims that constant negative reporting has an even more negative influence on citizens, especially in Goma, resulting in a vicious cycle and hindering the region’s pursuit of positive development.

Headless surrealism

Finally, Sarotava (2022) by Mahefa Dimbiniaina Randrianarivelo reflects the everyday life and struggles of the Malagasy people. ‘Sarotava’ means ‘mask’ in Malagasy, and this series depicts ordinary people going about their lives, but without heads. In his own words, “it’s about how Malagasy people live. Here you feel like you are in the middle-ages, and yet you have access to all the technology of the contemporary world. Your Maslow’s hierarchy of needs is all upside down. All these people in this series share that story. It doesn’t matter if they’re catholic, muslim, straight, gay, they are the product of the history of this land. You don’t need to know them personally to know each and one of them are trying their hardest, hence the absence of heads. And the future of this country relies on these people.” Randrianarivelo is drawn to the role of individualism in the evolution of contemporary society. Inspired by Rene Magritte and Man Ray, he is a surrealist who mainly works in photography.

Check out more images by the winners and shortlisted photographers here.