No others, same time in African Cosmologies. Photography, Time, and the Other.

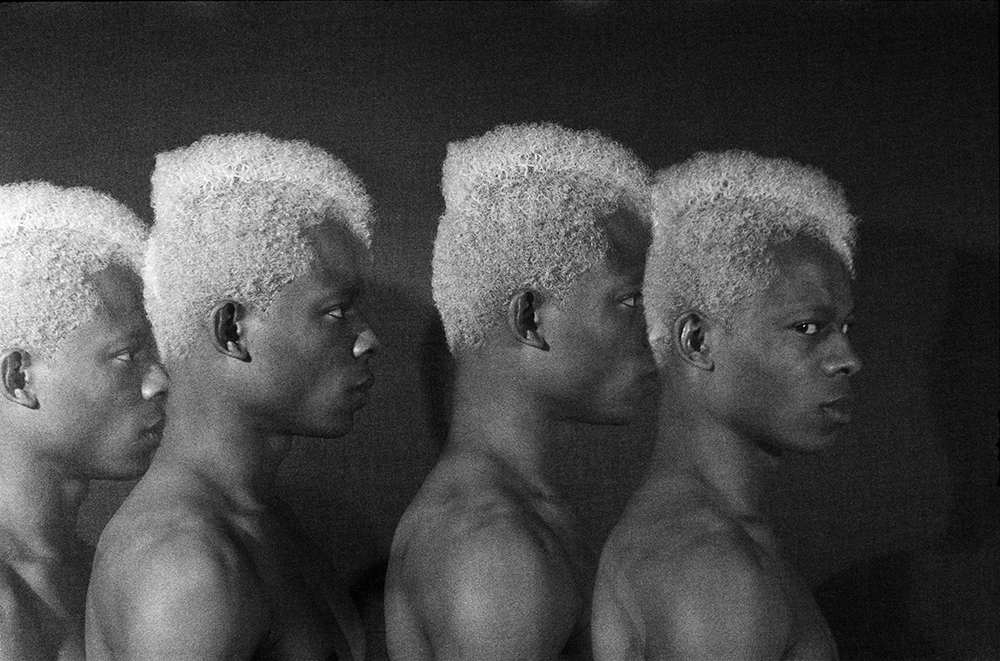

It is a beautifully produced book. The enticing image, Four Twins, by the late Nigerian artist Rotimi Fani-Kayode, overlaid by the imprinted title African Cosmologies, enhanced with titian metallic foil, creates an attractive case bound cover. Closed, the book triggers a sense of anticipation and curiosity that the click of an eBook simply cannot deliver. On opening this work it becomes immediately obvious that the print quality of the photography was prioritized, unique for a book that is heavy on essays and supplementary text. The thick colour trimmed pages do justice to the impressive photographs of thirty-three African artists.

The cover photograph Four Twins by Rotimi Fani-Kayode ties into the essay Photography and Substance of Image by the cultural critic and curator Olu Oguibe. The essay is a substantial twenty pages and was originally published in the compendium, The Visual Culture Reader, edited by Nicholas Mirzoeff (Routledge; London and New York). Its academic pedigree might deter some readers but perseverance is rewarded, as the essay is fascinating. It provides a concise chronology of photography’s early introduction to the African continent. The segment The Substance of the Image, which focuses on the Yoruba’s relationship with the camera, can only be described as a revelation. For unique dietary reasons the Yoruba have the highest birth rate of twins in the world. In the past the fragility of twins led to high infant mortality. Should the mother lose a twin she would employ an ancient ritual to honour the deceased twin, described by the by the British explorer Richard Lander in 1826 as ‘affectionate memorials’ or Ere Ibeji (‘twin images’). Originally these ‘replications’ were made of wood, produced by a sculptor, appointed by a priest who would sacralise the statuette on completion. The mother would carry this with her in the same manner as she would the surviving sibling. At one point in history – research suggests the late nineteenth century – the Yoruba began to use photographs as Ere Ibeji. There were no reservations in using an image of the living twin as a depiction of the deceased sibling. It was common practice that a female twin pose as a male in order to serve as a proxy for her deceased male twin. The techniques used by Yoruba photographers in creating surrogate images, which would be labelled misleading from a European perspective, are not only ingenious, but also reveal the Yoruba’s fluid approach towards the veracity of photography; they do not associate photography with objectivity, but fully embrace the possibility and inevitability of illusion. This is the direct opposite to Europeans who rely strongly on the verisimilitude of the photographic image. Olu Oguibe’s essay is perhaps a challenge, but it forces us to reconsider our relationship with the medium of photography. One could argue that the Yoruba instinctively adopted Roland Barthes’ photographic theories a century before they were published.

Christine Eyene, art historian and curator, provides the reader with a “travelogue” from Bamako while visiting the 2019 Les Rencontres de Bamako or the Bamako Encounters, Africa’s primary photography biennial. She takes the reader by the hand as she visits a range of exhibits. Our first encounter is Fixing Shadows, Julius and I (2018-2019), an impressive installation by Eric Gyamfi, composed of two thousand silkscreens and cyanotype prints ranging from A5 to A2. Muscow Ka Touma Sera (This is Women’s Era) is a moving display curated by Fatima Bocoum it features the work of Malian female photographers, which confronts the restrictive cultural conventions they must endure: the local girls high school, a well-chosen venue. Another novel installation is the family albums, made available by two families in their homes, a beautiful way to share the intimacy of Malian social histories. Eyene’s text is enlightening and entertaining, and a lot of the installations she refers to can be found online.

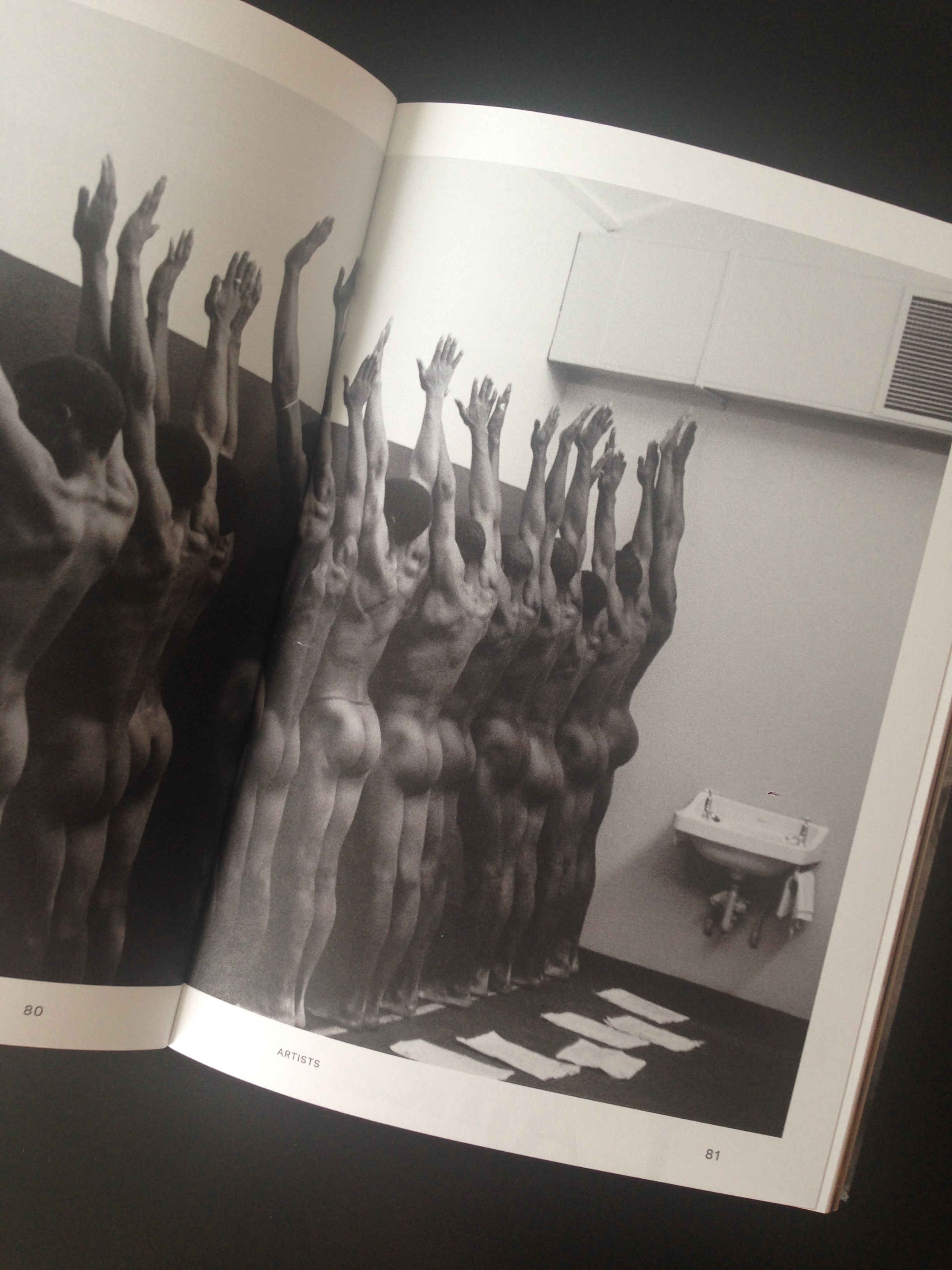

The thirty-three small portfolios of the African artists, which create the body of the book are all accompanied by an illuminating text and extensive captions. They are all equally impressive, however for this reader/viewer the South African photographers Ernest Cole and Zanele Muholi stand out. Their photography seems to interact; separated by five decades the images document two polar opposite periods of the same country, demarcating the punishing trajectory of South Africa’s history. Cole’s contribution to African Cosmologies is a small selection of images from his classic book House of Bondage published in New York in 1967 after he had to flee South Africa, the incendiary quality of the book sealing his status as persona non grata.

House of Bondage is the definitive book documenting apartheid. For me as a photographer it highlights the relationship between viewer and subject. The majority of photographers (including yours truly) come from a middle-class background, yet their work frequently focuses on the ‘other’. The people and lifestyles depicted are not the photographer’s own. In the case of House of Bondage, the photographer was directly involved in what is being photographed. It is extremely rare to witness photography where the photographer is one with his or her subject. House of Bondage is Ernest Cole’s life; this instills the book with a unique and chilling authenticity, the intimate relationship with his subjects defines the book.

This intense affiliation with his subject matter became evident when the Ford Foundation commissioned Cole to replicate House of Bondage in the southern United States. Cole had lived, breathed and immersed himself in the struggle against apartheid. Applying this depth and passion to another subject, however similar it might seem in the eyes of a white American editor, proved a challenge, and Cole was the first to admit that his work in the Jim Crow south did not share the same intensity as his South African images.

The gritty realism of Cole’s 1960’s account of apartheid juxtaposed with the stylized auto portraits of Zanele Muholi seems antithetical, yet both bodies of work share a deep sense of activism. The editor’s choice for this book is a photograph from a series of striking self-portraits titled Somnyama Ngonyama: Hail the Dark Lioness (2015). The artist confronts the camera point blank, wearing a miner’s leather helmet and goggles. The photograph honours the forty-four South African miners murdered by police during a workers strike at a Marikana mine in 2012. By casting the artist as co-worker, Muholi examines the collective violence, be it physical or political, that many South Africans encounter. As a non-binary South African self-identified ‘visual activist’ Muholi is challenged by the experience of living in a country where the rights of the LBGTQ community are violently abused despite South Africa’s enlightened constitution. Their photography – and filmmaking – celebrates and commemorates South African life in all its richness and diversity, and is intrinsically intertwined with contemporary political narratives.

The title African Cosmologies: Photography, Time, and the Other echoes Johannes Fabian’s publication Time and the Other: How Anthropology Makes its Object (1983). Fabian argues that anthropologist discourse relegates its subjects to another time: the anthropologist banishes ‘the other’ to a different temporal status than his own. This contradiction is instrumental to a concealed political agenda within anthropology, one that creates a discourse of otherness, thereby justifying colonial oppression of the ‘other’ in order to universalize Western progress. The labels ‘developing and developed world’ bear witness to this ghettoized interpretation of time. The ‘developed’ West represents completion; the rest of the world is not yet there.

The subtitle Photography, Time and the Other can only refer to photography’s complicity in the manipulation of time and its contribution to the colonial enterprise. The work of these thirty-three African artists should be viewed as the long overdue riposte to the colonizing camera.

Pieter van der Houwen is a photographer / documentary filmmaker who has worked extensively on the African continent. His book The Complicit Camera (to be published by ZAM 2021) is an account of how mechanisms within the media industry further the clichéd Western Perception of the African continent; van der Houwen does not shy away from his own culpability. The Complicit Camera is a personal reflection on how his photography has contributed to the ingrained Western perception of Africa.

African Cosmologies is published by FotoFest & Schilt Publishing.

Buy your copy of the book here.