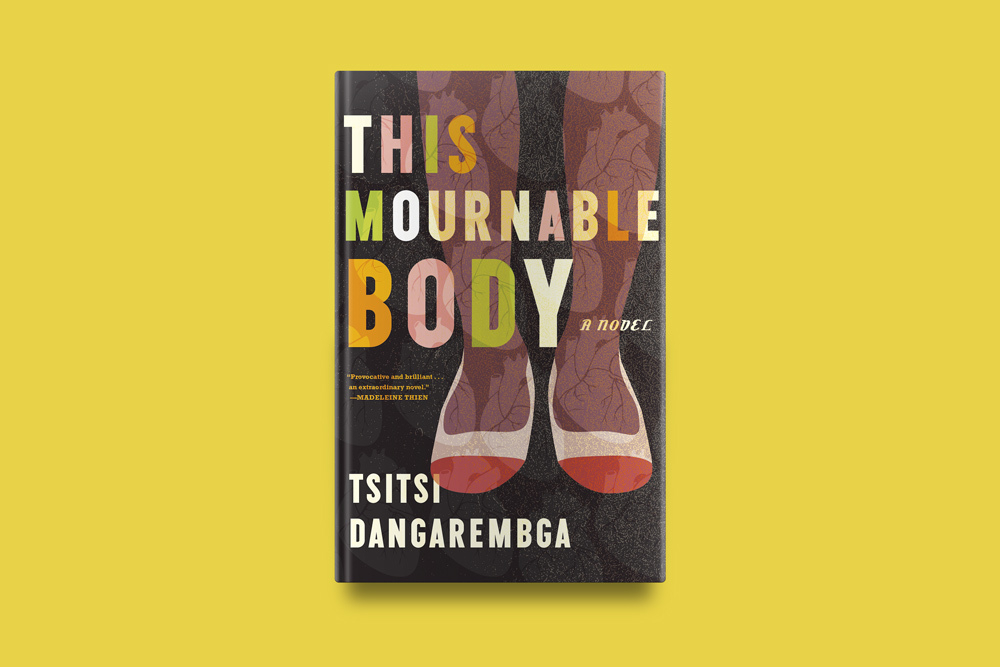

In Tsitsi Dangarembga's new novel, nominated for the 2020 International Booker Prize, shame and rage reign before the main character comes to terms with herself.

All is not well with Tambudzai, the protagonist of Tsitsi Dangarembga’s novel, This Mournable Body, a title inspired by the work of Teju Cole, Unmournable Bodies. We find Tambudzai or Tambu, in short, jobless in present day Harare, Zimbabwe. The novel is an extension of the seminal debut novel Nervous Conditions (1988), but the Tamba of that novel is the Tambu of this novel, as if a great transformation has taken place which, in fact, it has. Not only has the names slightly changed, but the character Tambu is middle aged now and adrift with nothing to hold onto in a city inhabited by lost women and men.

It all begins with a swift decision Tambu takes without giving much thought to the consequences. She leaves a well-paid advertising job, because she feels she’s not given credit for her hard work. It's her white boss Tracey, who was once her class mate, who gets all the credits. In Zimbabwe, a country with a history of inequality, the beautiful Tracy was very popular at school and seemed to score high grades without putting in much effort. Whereas Tambu, hailing from humble beginnings, manages to complete school thanks to the efforts of her uncle. This history of inequality haunts her all of her life and perhaps provokes that sudden decision, which she soon regrets. At the heart of this beautiful novel, set in current day Zimabwbe, is the story of how life unfolds for a middle-aged and unemployed woman without prospects, who’s too ashamed to share her present situation with her family in the village.

The novel is written in second person perspective, which is a difficult approach to sustain at such a length, but this does not seem to faze Dangarembga in the slightest. She excels in presenting to us a life that follows the decision when Tambu rents a room from a wealthy widow, whose children wants her gone by all means so that they can take over the property. Tambu who convinces the old widow she will soon have a job soon begins to worry about how the old woman would react when she discovers that she spends all her hours indoors, brooding on life.

There are people Tambu can turn to in the city, her cousin Nyasha, for example, who was educated in the West and who’s married to a German. But shame prevents her. There’s an innate tendency in Tambu to relish other people’s suffering, as though that would legitimize her own. But one day, after many failed attempts at securing a job that matches her competence, she manages to pull herself together once again and becomes a biology teacher at a secondary school. This subject is not her speciality, but competent teachers are lacking. Tambu’s sense of justice and her insistence on applying order at a school where popular girls have their say, results in her attacking one of those girls. The incident is an accumulation of all of Tambu’s rage and disappointment. She simply loses it, a reaction lands her in a mental institution where for the first time, she experiences that black and white people are equal, and where a white woman mistakes her for her daughter.

It's her cousin Nyasha, the same one from Dangarembga’s debut novel, who comes to her rescue at the end of her convalescence. She takes her home to live with them. The poverty of her cousin and her German husband shocks her. She had never imagined that white people could be so poor, but the German doesn’t seem to care.

The novel is an exploration of hopes and how vain they can be, for every time Tambu finds a tiny stream of expectations and begins to walk towards it, she comes to point where the light simply fades. One day she runs into Tracy who’s so enthusiastic about the meeting that she suggests that Tambu comes to work for her in a new company that sells the idea of ecotourism. The circle is complete. It is as if Tambu has reached a point where she has ceased to care. And here, at a place where she finally feels at home, Tambu takes a decision that has far reaching consequences not only for her but for all people who had invested in her.

The novel is a meditation on the foibles of life, and how uncertain our paths are, even those paths that we think offer the most rewards. It provokes; it is interspaced with instances that shock. And always in the background there’s the legacy of the war of independence, which shaped and continues to shape the trajectory of Tambu’s life and the country’s destination. The novel explores to great depths the psyche of a modern woman, the fears, the hopes and disappointments. It has its tender moments, especially at the end, when Tambu seems to come to terms with herself and accepts what is doled out to her.

Dangarembga is in supreme form in this novel and it shows on every page. The African novel is alive and it’s extending the boundaries of fiction in part due to works like this.

Vamba Sherif is a Liberian/Dutch writer. his debut novel Het Land van de Vaders was published in 1999. his last book, De Zwarte Napoleon, came out in 2015. His books have been translated in several languages.