‘We have become more of who we are because governments all around the world are showing us exactly who they are’.—Chuma Sopotela (Performance Artist & Theatre Practitioner)

Since the fall of Apartheid in 1990, South Africa’s arts sector has been recognized worldwide for its vast and revolutionary talent, fueled with a well-pronounced history of activism to fight the many inequalities in its society. South Africa, and more specifically, Johannesburg, is the African continent’s economic hub. It is also an entertainment and cultural home to many, from various parts of the country. This year, when Covid-19 spread quicker than wildfire, artists and cultural workers found themselves destitute, stranded, and rejected by the very government that claimed to support them.

An unequal economy

In understanding the state of the arts in South Africa, it is important to focus on the ailing economy the arts operate in. According to official statistics, the country’s economy is the most unequal in the world. The latest data show that the difference in income between the bottom and top earners is growing exponentially. High unemployment levels further compound those inequalities. To be exact, 6.7 million people are out of work, that’s 29% of the total population of working age. A week before the countrywide lockdown, South Africa’s credit rating was downgraded to junk status.

The full-scale countrywide lockdown caused by the Covid-19 outbreak led to South Africa’s economy grinding to a halt. Given the country’s context of inequality and unemployment, the prospect of food insecurity, ever-increasing unemployment, and deepening levels of poverty became an even more pressing reality. On the 21st of April, President Cyril Ramaphosa announced a 500 billion rand allocation, in trying to avert a crisis. A chunk of this budget went to the health sector, some of it went to hunger relief, and the residue was divided between smaller enterprises, tourism, and tax relief for companies.

The arts sector, which had already been struggling, will continue to do so unless there are measures and activities put in place to resuscitate it. The South African government has long been aware of the dire state of the arts: even before the outbreak of the pandemic, several activists called on the government for support and resources. But all of it fell on deaf ears.

Art as a priority?

The South African government has not been as stringent in saving the arts sector as one would expect, given the unique space the arts and artists hold in nation-building and social cohesion projects.

Even with all its ongoing struggles, the ‘Cultural and Creative Industries’ (CCIs) made a significant contribution to the country’s economy, with 1.7% of the total GDP, according to a government study from 2018. That same study showed that 7% of the national workforce came from the arts and culture community.

You could argue that there is a distinction between the CCIs and the ‘real’ cultural sector. In that case, these numbers don’t paint a proper picture of the arts’ contribution to the economy. However, this distinction is blurred. In reality, the two intersect. Contracted actors or actresses on big-budget television productions, are a perfect illustration. These are artists practicing their craft and earning a living, in a neoliberal and exploitative business environment.

Given these facts, Finance Minister Tito Mboweni prioritized an increase in funding for the arts in his 2019 Budget Speech. He emphatically argued that the arts could very well be seen as tools of ‘soft power’. This concept was coined by political scientist Joseph Nye in the late 1980s as ‘the ability of a country to persuade others to do what it wants without force or coercion’. One way this has been asserted culturally in Africa is through Dstv. This pay-TV service has enabled South Africa to export its cultural products in the form of music, news media, and soap operas, and thus to promote its national interests.

Criteria for relief

Eventually, on the 4th of May 2020, 150 million South African rand was announced as a relief for the arts and culture sector. Nathi Mthetwa, the Minister of Sports, Arts and Culture (DSAC), was criticised after leaked information uncovered that the criteria for choosing beneficiaries didn’t represent the entire arts sector. The government denies this and maintains that the criteria and distribution mechanisms of the relief fund were crafted in consultation with representative bodies of the different domains within the cultural sector.

In a candid response to the DSAC, award-winning freelance performance artist Chuma Sopotela did not mince her words: ‘We again have to beg our Minister to take us seriously and, in the meantime, I have to rely on other ways and money-borrowing to feed my family. Artists are not special citizens, we are just like all other tax-payers in this country, and we ask to be treated as such’.

Dancer and choreographer Mamela Nyamza has been vocal on social media platforms about her concerns around this Covid-19 relief fund. Nyamza, a teacher, mentor, and leader within theatre spaces, as well as an internationally recognised performer, lamented the South African government’s haste in pushing independent artists out of the ranks to receive funds during the pandemic. ‘Artists, you are on your own’, she exclaimed. ‘Over 90% of our artists did not receive any support from the DSAC. The few that did are connected, either technologically or politically. There was no transparency on the criteria used to select beneficiaries’.

Sopotela agrees: ‘The corruption happening in the Arts and Culture has crippled what should be one of the most income-generating sectors in this country. All this because we are served by ministers that don’t care and don’t know about the needs of the artists’.

According to the DSAC, the relief fund caters to artists who had scheduled events and projects with the national government, and who were able to render proof of their contracts with the various constituents in government. This response created a considerable problem for most artists, who may not necessarily be contracted by any specific entity or department and have had to rely on freelance work. The system deems many freelancers ineligible for the unemployment insurance fund since they fall under an independent statute. That’s especially frustrating since freelancers contribute 25% of their income to the South African Revenue Services for each paycheck they receive.

Those that fall outside

In Cape Town, the arts community is further disgruntled because the Department of Employment and Labour has completely disowned artists as a labour force that contributes to the economy. Scott Eric Williams is a visual artist based in Cape Town, who describes himself as an interloper, working autonomously, or as a freelancer or contractor. His experience has been one he explicitly describes as ‘precarious’. ‘Many of us slip through the cracks. I have applied for some independent funds, but the collective need is great, so I am still waiting on responses’.

But it’s not only freelancers that fell through the cracks of the support system. There is a giant need for support of women in the industry, specifically black and brown women in vulnerable situations. Providing safe and temporary shelter for victims of gender-based violence remains a concern.

Women In Arts requests, amongst other areas of concern, that the following two issues are highlighted and addressed. First, raising awareness about the impact of Covid-19 on the livelihoods of workers in the arts sector. Secondly, prioritizing and using the arts in assisting society to speak out and report cases of gender-based violence against women and children while under lockdown, a major issue in South African society.

Opportunities for the revolution

Carol Brown is a curator and influential voice in the art world, based in Durban, Kwazulu-Natal, the province with the first Covid-19 patient. Brown’s curatorial mission was always deeply steeped in advocacy, and in shaping contrasting and stark realities with the rich visual imagery of love and solidarity. ‘I regard this current crisis as an opportunity to reframe exhibitions, and to increase awareness of the social issues which a pandemic presents’. Brown also speaks out about the social and economic impact this pandemic has on audiences as well as artists, who have had their exhibitions canceled.

Likewise, Sopotela is convinced that artists will have to find new grounds to support their craft. What that entails, is yet to be understood. ‘As artists, we are left to fend for ourselves once again. As the informal sector that is yet to be formalized, we have to reinvent ourselves. That’s not necessarily a bad thing. In fact, we have become more of who we are because governments all around the world are showing us exactly who they are. Like in every revolution, there are at least two opposing parties. And one has to win. Right now, the artists have been called to war against the governing structures. This war needs to prove to those structures that the power always remains with the people’.

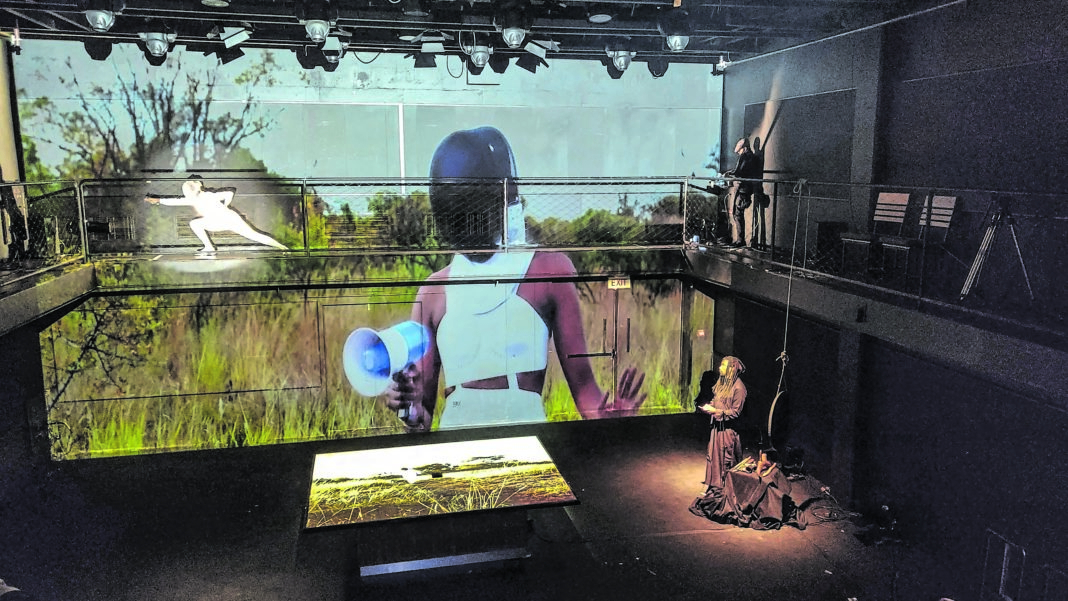

The creative arts as a whole have to move in a different direction. Arts organisations and communities have directed some of their activities online, posing profound challenges for artists who have earned their reputation and income with audiences across cultural spaces in South Africa. Tonderai Chiyindiko, a theatre practitioner and creative business consultant, calls this the beginning of a brand new way of interacting with audiences. He emphasises that the digital and virtual connections made between the artist and the audience were vital in maintaining the social aspect so crucial for the creative arts.

In her popular love song Weekend Special, late South African musical royalty Brenda Fassie sang about broken trust and unfulfilled promises. Similarly, artists neither want to be coddled through the pandemic nor be made to believe falsities about their fledgling relationship with the South African government. It cannot be that an industry that once helped bring down the Apartheid regime is completely obliterated while the government sits back.

Many of the artists above agree that a substantial amount of time should be spent on establishing a reliable, supportive, and professional body that thoroughly represents the varying interests of artists across the country. This body needs leadership that is trustworthy, reliable, and transparent in its efforts to provide the best relief for the industry.

Palesa Motsumi is the founder of Sematsatsa Library, a social events initiative focused on empowering the rich imagery and work of women of colour in the creative industries. She is a writer, communications practitioner by training and has worked as an art consultant. Motsumi is currently working on her first non-fiction book, titled, Mantsho.

Tariro Mudzamiri is a financial services professional based in Johannesburg, South Africa.