Since December of last year, the Moroccan artist Adam Belarouchia has been a resident at the Thami Mnyele artist studio in Amsterdam – much longer than expected, since all the flights home were cancelled. This is a portrait of a young artist, who gets his inspiration from the streets of Rabat.

It is a powerful image. Thami Mnyele, painted in black and red, with a halo of eleven holes around his head. Moroccan artist Adam Belarouchia (26) reveals his work in the Amsterdam studio where has been staying since December last year, as an artist in residence.

In the portrait, a homage to Mnyele, who was killed the 15th of June 1985 by South African soldiers, Belarouchia included many symbolic features. Such as the white rectangle before Mnyele's eyes, signifying his innocence. Or the black holes, representing the eleven other victims of the brutal attack – artists, journalists and visitors of Mnyele’s house – exactly 35 years ago. And the big flames coming out of his hand, like a secret weapon.

It gives Mnyele the look of a superhero, I suggest to Belarouchia. He smiles. ‘Maybe it is the influence of my background as creator of comic books’, he says politely. Then he walks to the living area of the studio, to show, in a catalogue of Mnyele’s work, a poster designed by the South African artist. It is the logo of the Culture and Resistance symposium in Gaborone (Botswana) of 1982: two hands, with flames coming out, as if it is a burning torch. This poster formed the real inspiration for the flames, he explains.

Around the dinner table, a conversation unfolds about art and identity within the small group of visitors who came to see the painting. Generally speaking, Belarouchia says, Sub-Saharan Africans see Moroccans as Arabs, while Middle Eastern Arabs see them more as Berbers. ‘While Berbers see me as too urban and not really connected with the original traditions’, Belarouchia chuckles. ‘I am everything and nothing at the same time. But I do not feel quite comfortable with it.’

‘I grew up in poor suburbs and I still identify with the low brow’

Traditions were also important for his teachers at the Fine Arts School of Tétouan where Belarouchia graduated in 2018, he adds, at the department of Comics and Graphic Design. ‘They hold the French-Belgium tradition of making comic books in high esteem, but paid little attention to manga, animé, or the American comics we students talked about all the time.’ Belarouchia grew up in a poor suburb of Rabat. ‘My whole life I have there; I identify with the low brow. It would feel hypocritical if in my work I would focus only on Moroccan tradition or the art elite’.

Bart Luirink, editor in chief of ZAM Magazine and one of the guests, observes ‘similarities with the life of Thami Mnyele’. ‘Not denying your identity, nor the place where you are from, but at the same trying to raise above the social structures that you are used to. Belonging and at the same time not belonging – that was the story of Thami Mnyele’s life as well’.

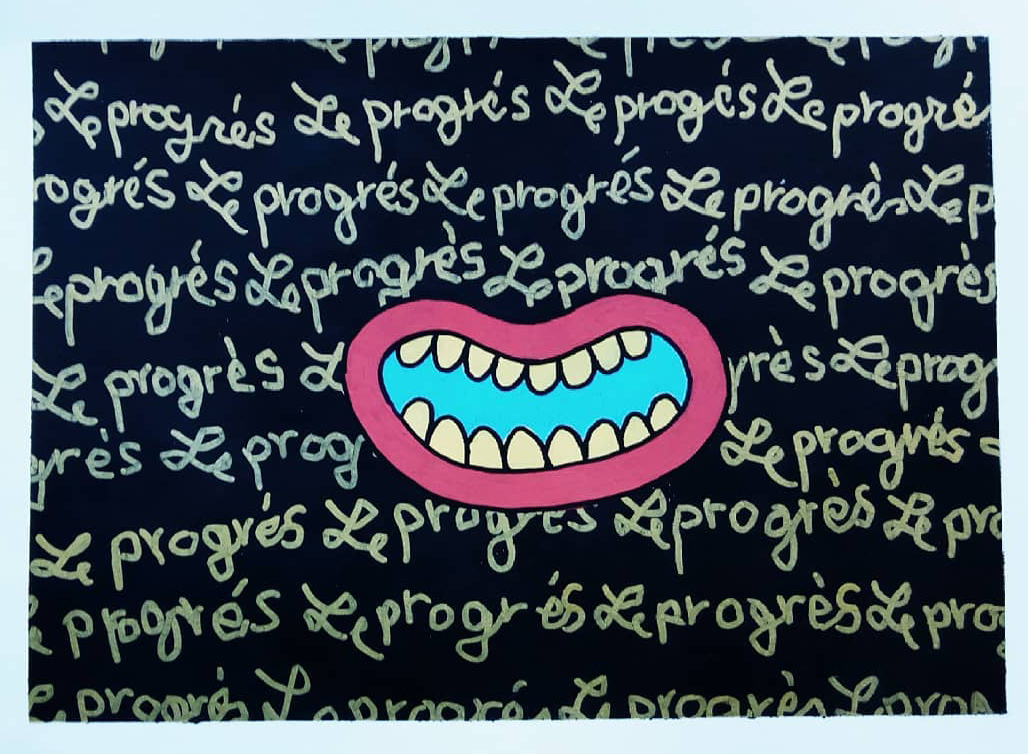

There is another similarity: both artists' feel a strong desire to comment on society through art. Belarouchia's graduation project, for instance, is a clear critique of the atmosphere and discipline in Moroccan primary schools. In the comic, Belarouchia drew a pupil, arriving at school for the first time, literally as a happy looking walking mouth. After a while, a teacher grabs him and pushes and pushes – until the boy gets the shape of an ear. ‘There is this custom in Morocco, which is not necessarily negative, that if the teacher yells “I say” the class answers “I hear”’, Belarouchia explains. ‘Everybody knows it. So I called my project “I hear” in Darija, the Moroccan language’.

Although at school he usually got high marks for his graduation project, he got the second lowest mark in his class. ‘The work is a comment on primary schools, but I am afraid my teachers thought I was talking about them’, he says with a smile.

In later work of Belarouchia, scars keep coming back, as a symbol for the tough guys who live in the suburbs of Rabat where he grew up. ‘They are half criminals, but sometimes also very religious, which does not stop them drinking alcohol. They just say: I hope God forgives me’.

Most of the ‘tough guys’ had scars from street fights they'd once fought. ‘Our parents taught us to avoid them, but we looked up to them and imitated them, already in primary school: we drew scars on our arms or even stuck adhesive tape on our skin in such a way that it looked like a scar’.

During the conversation, Belarouchia receives the message that Morocco is closing its borders, precisely on the day his return flight is booked. He cannot go back home, to his family, not even during Ramadan, it turns out. Even worse, he gets ill for two weeks – coughing, feverish, possibly Corona. But he recovers, finds some wooden panels on the streets of Amsterdam, and is working with them.

When I pay him a new visit in May, I see him spraying black paint on the panels and then removing the paint a short time later. ‘The outside of the spot, where the paint is thinner, is already dry’, he explains. ‘But the thicker paint inside is still wet, and therefore easy to remove.’ On those spots, the wood shines through the paint again, making the whole panel look more like the old, used wooden desks one would find in public schools in Morocco, he says.

'At school, the wooden desks of the tables were heavily marked with carved or written names’, he continues. ‘That is what I want to recreate in this work, on these wooden panels. Most of the desks have been replaced now, by cleaner, more durable ones, with polyester coatings. That is fine, of course. I do not think the old desks were better; it is not out of nostalgia that I want to recreate them in my art. No, I just want to document it'.

‘In my country, everything inside you do not touch’, he elaborates. ‘But as soon as you are outside, the street is your canvas. Everywhere you see drawings, names, graffiti. Most of the time it is about soccer, love, religion, or revenge. I use that in my work’.

Though Belarouchia would have preferred to be with friends and family, especially during Ramadan, he does not complain about ‘getting stuck’ in Amsterdam. He is grateful that the Foundation allows him to stay, others are far worse off than him, he emphasises. It is true that he can’t go out and visit people, museums or gallery-openings, but that does fit quiet well with his personality, he confesses. ‘The networking and meeting prominent people in the Dutch art scene was an important part of my first stay in the studio of the Thami Mnyele Foundation’, he remembers. ‘But after three weeks I was exhausted, to be honest. I am glad about the experience, you need networking if you want to succeed as an artist. But I feel better by myself, working alone in the studio’.

Being inside the whole time is not a big problem, he says. ‘As a kid, we grew up in a very small house. My brother and I shared a bed: he was always sleeping behind me, in between me and the wall. After we moved, he got his own bed. I missed him; his presence always made me feel safe. So no, I’m not afraid of getting claustrophobic’.