This month 35 years ago, South African death squads ended the life and career of artist and activist Thami Mnyele. Since 1990, an Amsterdam artists residence welcomed 127 African artists in his honour.

‘I liked him from my very first meeting. He had vision, was talented and skilled. A great organizer and fundraiser. In 1982 in Botswana he set up the most important artist's conference South Africans has ever held. For the first time, they discussed their future, without their skin colour playing a role.’

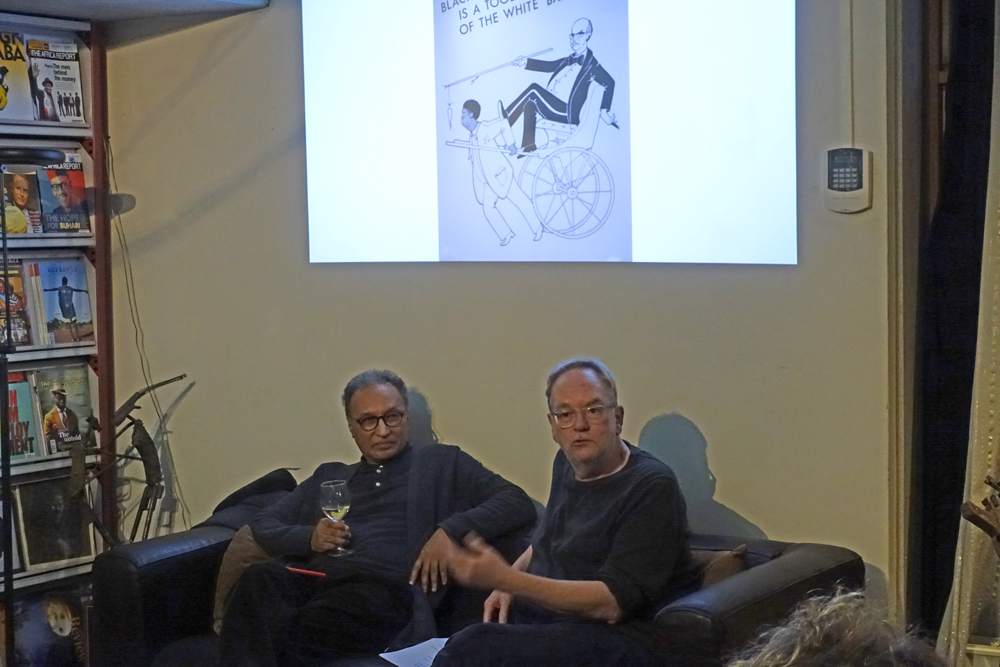

The South African artist Gavin Jantjes (1948) fondly remembers his good friend Thami Mnyele in a packed office space in Amsterdam, where ZAM Magazine is located. The event he takes part in this January afternoon is a tribute to Mnyele, who was murdered by South African soldiers, but also to the jubilant Dutch foundation that bears his name and organized this event with ZAM. For thirty years, the foundation has offered artists — initially only from South Africa, then from the rest of Africa and the diaspora as well — a residence in Amsterdam for several months, to deepen their career, knowledge and network.

To what extent did the Thami Mnyele Foundation contribute to the rise of African artists? How do former residents look back on it? And how much do they have in common with Mnyele? A striking amount, according to conversations with those involved. A private visit to exhibitions in lockdown shows the resemblance as well.

If something characterized Mnyele, it was his belief that artists should always play an active role in society. He even considered taking up arms and even got military training at an ANC camp in Angola. He always spoke of it when he saw Jantjes, who lived in exile in Germany from 1970 and later in London, where Mnyele came to stay.

In Germany, Jantjes had come across the drawings of Käthe Kollwitz (1867-1945), who ran a doctor's practice with her husband in a working-class neighbourhood in Berlin. ‘Her statement is Jede Gabe ist eine Aufgabe, if you have talent, you have to use it for humanity’, says Jantjes from the sofa on which ZAM editor-in-chief Bart Luirink interviews him.

‘That's how artists should stand in life, I thought. Thami felt the same way, but he said: if we are attacked with military hardware, we cannot strike back with poems. Gandhi's philosophy suited me, but it didn't suit Mnyele well. As an ANC comrade, can I still be an artist, he always wondered. No, I said, then you are an ANC cadre, and that's where being an artist ends. He constantly struggled with that. That touched me’.

‘They will never do anything to me’, Mnyele said.

Jantjes visited Mnyele in 1982 in the Botswana capital Gaborone where he led a flourishing artists' collective, with many other exiled artists, poets and musicians. Already during this first meeting, Jantjes, a political refugee himself, saw the risks Mnyele ran. ‘At the airport in Gaborone, where Thami picked me up for the conference, a man in the toilet was staring at me all the time. "Oh, that's a South African agent," said Thami. "He always follows me." When Thami got into his Volkswagen Beetle, he shouted to that agent from the footboard "I'm going home, you can follow me home." I did not know what happened to me, I was nervous. They could kill you, I said, but Thami wasn't scared at all. "They will never do anything to me,”’ he said.

But Mnyele was wrong. In the early hours of June 14, 1985, a South African military death squad entered Mnyele's house, the soldiers ripped his drawings from the wall, emptied their machine guns on those present and onto the artwork and detonated a hand grenade as a farewell message. Twelve people died: artists, journalists, visiting guests, a six-year-old boy.

The international outrage about the cross border operation was huge. So huge that, to justify the attack, the commander of the operation hastily borrowed weapons to show to the press in South Africa claiming they had been 'discovered' at the compound. Years later this became evident in testimonies before the South African Truth & Reconciliation Commission.

Jantjes: ‘I had arranged a grant for Thami at the art academy in Oslo. If he had accepted the offer — he only wanted to go if his family was allowed to come with him — he would still be alive’.

The fifty participants in the Studio ZAM tribute to Mnyele this January, some sitting on the desks, are listening closely. When some video footage of Mnyele is shown, Bert Holvast (73), co-founder of the foundation, takes the floor with a broken voice. ‘It still hurts to see him alive and well. This smart, young, talented man stayed with us’, he says, recalling a week in 1983 when Mnyele attended a conference in Amsterdam.

Holvast took long walks with Mnyele and went with him to the Rijksmuseum, where he only wanted to see one painting: Rembrandt's The Mother. ‘Thami kept looking at it for minutes. After that we walked in the city for hours, talking not about art or the struggle against apartheid, but about our mothers, brothers and sisters. He was convinced one day he would return to South Africa’.

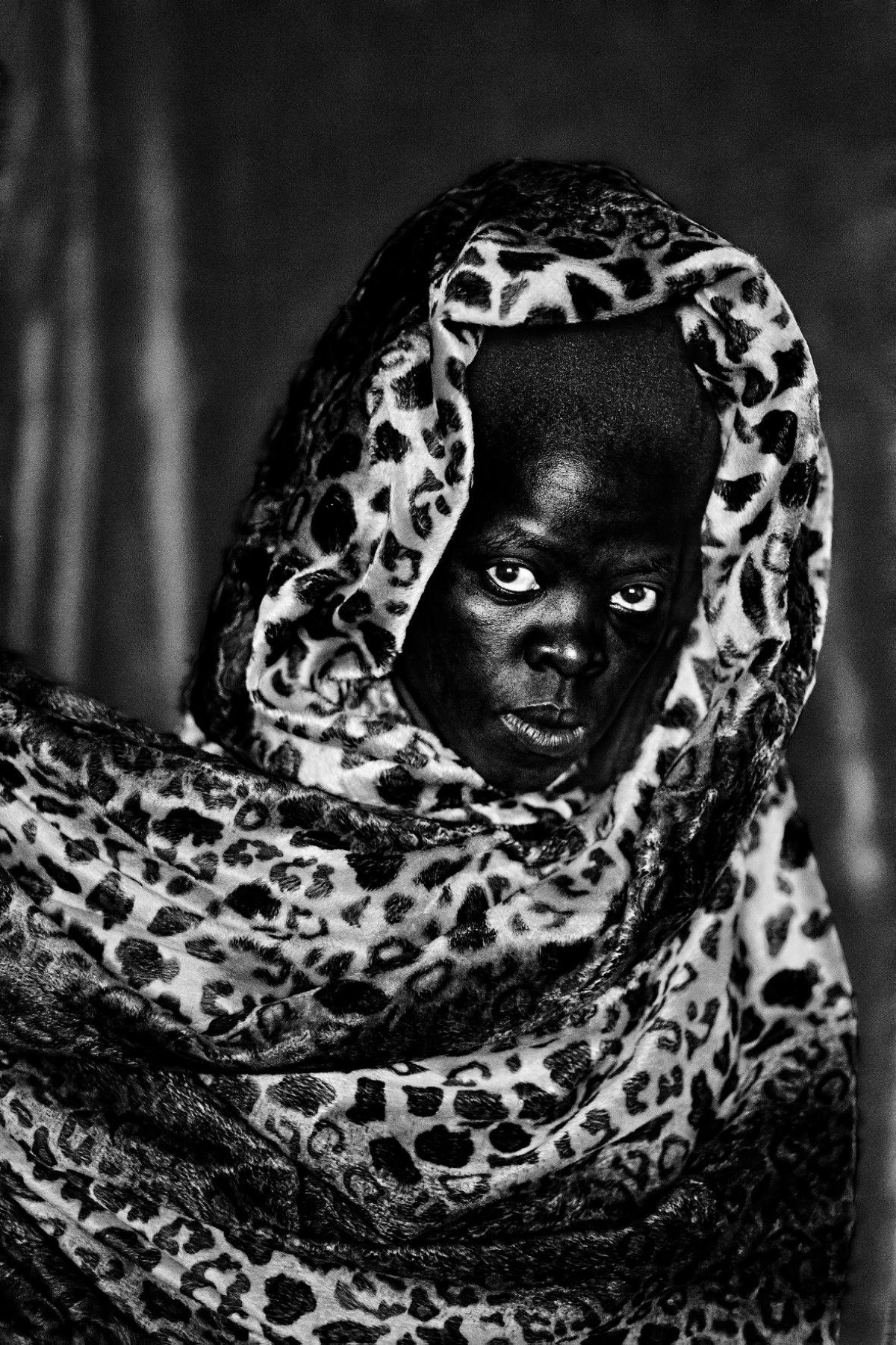

Then Holvast conjures up flowers for Pauline Burmann, chairperson of the board of the foundation, who has been involved since 1993. Partly under her care, 127 artists found their way to the artist residence, and then many of them to the international art world. Such as ‘visual activist’ Zanele Muholi, the famous South African photographer who had a solo exhibition at the Amsterdam Stedelijk Museum two years ago and who is exhibiting at Tate Modern in London from April 29 this year. Such as Abdulrazaq Awofeso from Nigeria and Guy Woueté from Cameroon, whose work only recently can be seen again in exhibitions in Amsterdam and Arnhem, after three months in lockdown. Such as Sharelly Emanuelson from Curaçao, who won de Volkskrant Visual Arts Prize in March for her work shown at the Stedelijk Museum Schiedam. And like the young Moroccan artist Adam Belarouchia, the current resident of the studio — who may break the residence record, because he cannot return to Morocco due to the corona crisis.

‘The foundation is a pearl, a mustard seed that blossomed’, says Holvast, when I call him later. It was a proposal by Holvast, then councillor for the GroenLinks party in Amsterdam, that laid the foundation for the artist residence. It was early 1989, the cultural boycott against Apartheid South Africa was still in full force, says Holvast. ‘That was a necessary, but blunt weapon, with a very dark side: you shut people off from international cultural life. Let's break that open, I thought. After saying "no" to South Africa for years, let's emphasize the "yes" side and give space to artists’.

At that time, Amsterdam financed a studio in New York, where Amsterdam artists could work for a while. In analogy, Amsterdam should open a guest studio for South African artists, Holvast argued. ANC leader Nelson Mandela was still in prison, and apartheid was under attack more than ever. ‘Everyone wanted something to do with South Africa. My proposal for a guest studio was immediately adopted: we received 24,000 guilders on an annual basis’.

‘This artist residence is a gift to Amsterdam’.

In a vacant school in the Kinkerbuurt, a neighbourhood in central Amsterdam, two classrooms were converted into a studio and living quarters. In May 1992 the first two South African artists arrived. ‘I remembered Mnyele when we were looking for a name for the foundation and residence. It had to symbolize all that smothered talent that had no chance to develop during apartheid’.

Mayor Ed van Thijn came to open the studio: on his bike, at eleven in the morning, despite his busy agenda. ‘The artists he welcomed could hardly believe that this was the Lord Mayor of Amsterdam. I still have the speech, where Van Thijn added things by hand. The studio is “a gift to Amsterdam,” he said, enriching the city. Magnificent’.

A white tile panel with the text Openbare Basisschool der 1e klasse – Public Primary School of the 1st class – adorns the brown brick building in the Bellamystraat where the studio is located. A row of doorbells with nameplates is reminiscent of a student house, the corridor and the wide stairs, with high ceilings full of peeling paint resembles more a neglected squat. That doesn't apply to the studio, where Adam Belarouchia, a man in his twenties with of a small beard and soft, dark eyes, opens the door. Sleek whitewashed walls, a sofa, a cabinet filled with art books and a staircase to a bedroom mezzanine are the first sight. Beneath the mezzanine is a small kitchen, and beyond this the studio: a bright room with a floor full of paint splashes.

It is March 13, a day after the Dutch cabinet announced an 'intelligent lockdown' for The Netherlands. Belarouchia would launch the work of art that he made on the request of the foundation because of its 30th anniversary. However, a number of invited guests stayed at home, out of fear for the corona virus: there are only five of us, including chairperson Pauline Burmann.

It makes the launch no less impressive. A two-meter-high portrait of Thami Mnyele, painted in dark red and black acrylic paint, hits you from the wall in the studio where it is hanging. A white block is painted over Mnyele's eyes, symbolizing his innocence; around his head one sees eleven bullet holes, like a halo, symbolizing the other eleven people who died during the attack in Gaborone, Belarouchia explains. From one hand fire is flaming.

He takes the catalogue of the major retrospective of Mnyele's work, in Johannesburg in 2008, and points to the poster Mnyele made for the 1983 Culture and Resistance Conference, which Jantjes already referred to in January: two entangled hands with flames, as if they form a torch. ‘This inspired me for the work’, Belarouchia says.

The catalogue features Mnyele's activist posters, full of raised fists and guns, as well as his surprisingly subtle, almost dreamlike drawings — a half-depicted woman dropping a ceramic pot (Things Fall Apart, 1978), a man half-hanging over barbed wire (Consequences, 1980) — all executed in gossamer lines and dots.

There is also a wonderful essay by Mnyele. He writes about his dream of becoming a good artist, about the theatre group he helped to set up and the lyrics of Malcolm X that he recited during its performances. ‘Whatever artistic indulgence we engage ourselves in’, Mnyele writes, ‘we (artists) must not be blind to the river of life within and around us, the social stream from which arts feeds and is nourished: the community’.

This ideal fits well with Belarouchia, who in his graduation project commented on the strict discipline in Moroccan primary schools. In a comic strip, he drew students who came to school as big walking mouths, but who were pushed and shaped into round ears by gruffly teachers. The comic was shared more than a thousand times on the internet, he says, but after always getting high marks, he just barely got a pass for this work. ‘I was commenting on primary schools, but I'm afraid my teachers thought I was talking about them, about how they were teaching’, he smiles.

In later work, scars recur, the hallmark of the tough guys who controlled the suburb of Rabat where Belarouchia grew up. ‘They were half criminals, although they never committed robberies in their own neighbourhood, but also tough, sort of heroic guys. Almost all of them had scars from street fights. We looked up to them, already in primary school, and drew artificial scars on our arms’. Also, other symbols and slogans that he finds on the street show up in his work. ‘The graffiti always concerns only four things: love, religion, football and revenge’.

With this street art theme he draws attention, says Burmann. ‘Modern art in Morocco is known for its large canvases with beautiful, abstract shapes’, she says. Then, looking at Belarouchia straight: ‘Your work is totally different. That's why we selected you’.

Burmann, who studied African contemporary art in London, strongly condemn the phenomena that all the art from Africa is tarred with the same brush, also in group exhibitions, while each country produces completely different art and artists. ‘We always focus on the work, not on supposed traditions’, she says of the work of the selection committees, which choose two or three candidates for the studio every year, from sometimes four hundred applications. ‘Our committee therefore preferably include people who have never been to Africa, to prevent bias’.

The applicant's motivations differ hugely. ‘Sometimes an artist sent some photos of his work, with a few lines only. "I am a confused artist", was all one of them wrote, fort instance. But we also received a glossy catalogue with all the candidate's work. The first artist was invited, the second was not’.

In addition to accommodation, two bicycles, a monthly fee of 850 euros and a free Museum Card, the foundation facilitates numerous meetings in the art world. However, there is no pressure to produce or exhibit work. It is one of the 'unique selling points' of the foundation, says Burmann. ‘It almost always works out. Once we had someone who was laying drunk on the couch for three months. But ten years later, he wrote that his stay here has changed his life and now he is the director of an art institution’.

There are also always many Dutch artists, curators and art teachers who invite the guests of the studio to gallery openings or art fairs. ‘During the hours in the train, while going to the TEFAF fair in Maastricht for example, they have exciting conversations about art and life’. Burmann finds this cultural exchange of ideas and contacts the greatest strength of the foundation. She recalls Krishna Luchoomun from Mauritius, who met Liesbeth Bik and Jos van der Pol here, better known as the artist duo Bik Van der Pol. ‘Thanks to him, the two were invited to exhibit at the Mauritius Pavilion at the 2015 Venice Biennale. Isn’t that great?’

The art biennials, especially those in Venice, are what Burmann calls ‘the Olympics of art’. The 1993 edition, when South Africa was allowed to fill a pavilion after years of isolation, would lead to the foundation's first major achievement: organising the exhibition Zuiderkruis – Southern Cross – in the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam.

The white minority regime wanted to prevent the exhibition

During a second conversation in mid-April with Holvast in his small vegetable garden in Amsterdam-Noord, he has a bag ready with clippings about the exhibition. Holvast: ‘I visited the biennale in Venice and spoke to many of the 27 artists whose work was on view, a truly multicoloured crowd. How nice would it be if everything could be seen in the Netherlands, I thought. Director Rudi Fuchs was immediately in favor and offered to make the new wing of his Stedelijk Museum available for it. That night I was almost filled with joy’. However, the organisers in South Africa, still part of the old apartheid guard, became concerned. They were in charge in Venice, but wouldn’t be in Amsterdam – and they feared that ‘Southern Cross’ would become ‘a political exhibition’, an 'ANC party.' Holvast: ‘That's what a South African official literally said to me’.

While preparations were already underway, the then South African Department of Foreign Affairs stated that the exhibition could not go ahead in the Netherlands, for bureaucratic reasons: contracts, insurance conditions and the wish of 'some participants' in the Venice biennale to get their work back 'as soon as possible'. Holvast immediately informed the press about the obstruction ‘and Fuchs wrote a great letter to the South African ambassador’. The letter is indeed a fine example of decisiveness. Fuchs writes that he found the quality of South African art at the Venice Biennale ‘surprisingly high’. Given the ‘multicoloured character’ of the participating artists and the historical role of Amsterdam as a city that took a stand against Apartheid, he had expressed ‘the strong feeling that the exhibition should come to Amsterdam’. Responding to the letter from Foreign Affairs he writes: ‘I have studied the objections mentioned with great care, and I have to say that I find them largely irrelevant’, he writes. ‘From a professional point of view, it is difficult for a museum to take these objections seriously, and one wonders if there are no other, veiled motives to prevent the exhibition from coming to Amsterdam’. He concludes subtly that the Amsterdam exhibition serves the goal of ‘the cultural and commercial cooperation that your country is supposed to pursue, now and in the future’.

South Africa gives in, the exhibition comes to Amsterdam, and Holvast gets money from all corners of the land to bring over some of the artists, of whom a selection was made by Burmann. The Queen’s husband, Prince Claus, opens the exhibition – creating much publicity and a huge increase of the attendance. ‘For the first time I see a major amount of black visitors in our museum’, Fuchs says with satisfaction to Holvast.

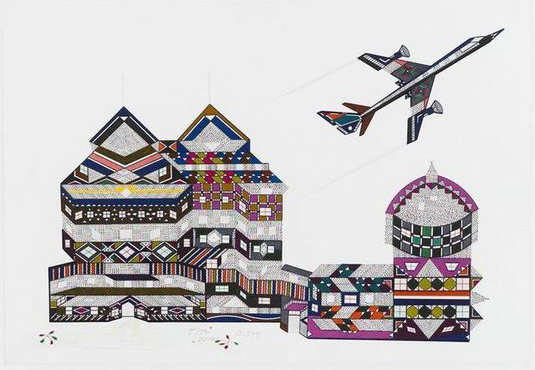

The evening of the closing day of the exhibition Holvast walks through the halls with Fuchs. He wants to buy one work for the museum, says Fuchs, and points to a small painting by Tito Zungu (1939-2000), called Plane and Building.

Holvast: ‘How much should it cost, he asked me. I was not really able to come up with an answer but I immediately mentioned a huge amount’. They agree on two thousand guilders. But Zungu was already on his way to Schiphol to catch his return flight. Fuchs walked to the cash register of the museum and has two thousand guilders counted out in small denominations. After that, Holvast rushes to Schiphol Airport and immediately gets permission from Zungu for the sale, who is very happy with ‘fantastic’ amount of money he earns for it. ‘Imagine’, says Holvast, almost lyrically. ‘Zungu was a poverty-stricken artist from Durban who had never travelled before. He was at the bottom of our list of artists we wanted to bring to the Netherlands, and he was the last one we managed to arrange the airticket for. And his work was bought by the Stedelijk!’

Ever since, more ‘alumni’ of the studio have received assignments as a result from their stay in Amsterdam. Like Abdulrazaq Awofeso (42) from Nigeria, who met curator Manon Braat when he stayed in the studio in 2018. Last year she asked him to make an installation for the exhibition City Life in De Kerk, the temporary housing of Museum Arnhem. Eleven artists give their views on changing cities, or on ‘people and urban reality’. ‘It was Awofeso's work that gave me the idea for the entire exhibition’, says Braat. ‘I never actually told him that’.

When I visit The Church with special permission in mid-April, the sun falls through the church windows onto the stone floor where the altar once stood. Now the place is covered with two thousand and twenty males and females, made of painted pallet wood. The figurines, each about ten centimetres high, form an overwhelming, colourful feast for the eyes.

From the benches in front of the choir, put on the lower church floor, I look at their faces for a long time. Some of them seem happy, some sad, some puzzled: wherever I look, I see something new. Suddenly I realize how wonderfully – though unintentionally – the work fits in with the corona-era: all 2020 figurines keep one and a half meter distance from each other, proportionately speaking.

Awofeso's work is called Gross Domestic Populace. It means to show that behind the Gross National Product, the eternal measure of economic growth, ‘there are always people’, Awofeso says by phone from Lagos. He worked on it for three months, with seven people who normally offer themselves as day laborers, without an art background. Each face was given a slightly different expression, ‘because we humans are all different’.

Welkom, the solo exhibition of Guy Woueté from Cameroon, who stayed in the studio in 2006, is as impressive as Afowoso's work, be it for other reasons. The exhibition closed a week after it opened in De Brakke Grond in Amsterdam due to the corona crisis. The ‘alleged objectivity of history’ is one of the main themes in this work, curator Vera Bertheux says. That certainly is shown by his video installations on display.

In two of them, two residents of the Congolese city of Lubumbashi take a bird's eye view of the history of Congo and Africa, while walking through homemade museums. For one, a Belgian who lived in Congo after independence and who calls himself a ‘white with a black heart’, all black leaders of the struggle for independence are great heroes. The other, a black, younger ‘guide’, condones colonial times. ‘You cannot enter the colonial past through one door’, explains Woueté from Antwerp, where he now lives. ‘Multiple views are possible’.

Awofeso and Woueté would have gotten along well with Mnyele. Awofeso ‘likes politics’ and likes to comment, although he does not want politics to take over his work. ‘I mainly express myself on Facebook and Twitter’, he says.

There is no ‘real freedom of expression’ in Nigeria, he continues. ‘Critical people I grew up with suddenly start praising the ruling party as soon as they start working for the government. Friends warn me to be careful. But I don't care about the risks. There should always be freedom’.

Woueté also believes that an artist should not ‘make work outside the context of society’. Art needs to raise awareness, he says; a 'little bit more justice' in South Africa is necessary, he adds a moment later; migrants really don't come to Europe 'to lie on their backs here', he states — all these themes come up during a long phone call from Antwerp, where he now lives.

Woueté feels fine in Belgium, ‘where you can be different and still belong’. That is what he missed in the Netherlands. ‘You are alone together’, he says of the individualism in The Netherlands.

However, he is full of praise for his time in the Thami Mnyele studio in Amsterdam. The most important thing, he says, was that he was given complete freedom. ‘At other artist residences, such as in France, they kind of expect you to tell the world how great they are to allow you to work there. Nobody at the Thami Mnyele foundation asked for that kind of gratitude’. He also enjoyed all the meetings and museums, especially to see the Aardappeleters – the Potato Eaters – from Theo van Gogh, which he ‘finally could see in real life’. ‘The painting says a lot about the working class in the Netherlands and is still relevant for the fight for social justice today’. Awofeso also praises the foundation for the contacts after his stay. ‘I continued to be in touch with Pauline and others, which I benefit greatly from’. This year, he again stayed in the studio for a week, around the opening of City Life.

The day of the conversation, two thousand Israelis in Tel Aviv march against Prime Minister Netanyahu. They stand together at a safe distance, observing the corona regulations. ‘Wow, it seems like a performance of my work’, Awofeso responds when I forward to him and Burmann an aerial image of the demonstration. ‘What a wonderful visionary he is’, says Burmann.

Burmann can not look into the future herself. For example, she has ‘no idea’ whether the structural grant by the City of Amsterdam the foundation gets will be extended after 2020. But if the money dries up, she has a solution, she jokes in an email with the self-portrait that Zanele Muholi made in the studio in 2006. ‘Look at that floor: if we are broke, we cut it into pieces and we will sell it through crowd funding’.

The exhibitions Welkom in De Brakke Grond in Amsterdam, City Life in De Kerk in Arnhem and the retrospective Zanele Muholi in Tate Modern in London can be visited until 12 July, 23 August and 18 October respectively. This year, the Rijksmuseum, the Amsterdam Museum, ZAM and the Prince Claus Fund were invited to select an artist from an African country or the diaspora to stay in the studio of the Thami Mnyele Foundation, in honor of its 30th anniversary. Chairman Pauline Burmann received a ‘Royal Knighthood in the order of Orange Nassau’ on April 27 for her contribution to the Dutch art world. Adam Belarouchia is still staying in the studio, waiting for the ban on flights to Morocco to be lifted.

This article was first published in Dutch by De Groene Amsterdammer.