Guy Woueté from Cameroon, now living in Antwerp, makes art. More to the point: he creates moments for contemplation. Welkom/Welcome in De Brakke Grond in Amsterdam has now reopened.

It is a rather strange experience. After entering Guy Woueté's exhibition in the Flemish Cultural Centre ’De Brakke Grond’, I hear a radio interview from hidden speakers. ‘Fascism is not an opinion, it is crime’, says a voice with a German accent. ‘Yes, but I can say I disagree’, answers a second voice. ‘And that’s an opinion.’

Then I step into the installation State of Nations – on my socks, because it is obligatory to take off your shoes here. I walk around on a carpet of artificial grass, which tickles my foot soles, and take a seat in one of the two West-African wooden folding chairs. They are always more comfortable than they look. I see a mirror on the wall. In huge capitals it reads: ‘Fragile but not made in China’.

Here I am, by special permission – because due to the corona pandemic, Welkom was still closed – and immediately I find myself thinking about issues like freedom of speech (and if it should have limits) and the vulnerability of human beings. The mirror, no doubt, plays with the experience with cheap products from China, but I can only think of how the coronavirus, which forced this exhibition to be closed after only one week, has shown how fragile we as a people are.

‘Woueté is driven, he wants to put issues on the agenda but does not want to impose his opinion’, Rogier Payens from De Brakke Grond had said, after he had opened the door for me. ‘He makes you think for yourself’, Vera Bertheux, the project manager of the cultural centre who organised the exhibition, added later. ‘In his work he puts question marks around issues like the supposed objectivity of history. You ask yourself: what is history? That's what makes it so interesting.’

Two video-installations in Woueté’s Le fou postcolonial insane illustrate this perfectly. In them, two residents of the Congolese city of Lubumbashi take a bird's eye view of the history of Congo and Africa, while walking through their own, homemade museums. One is Joseph Léonard Rohoyasimba, a white Belgian who has been living in Congo since before independence and who calls himself a ‘white with a black heart’. For him, every black leader of the struggle for independence is a great hero – and maybe he sees himself as one too, because he has added ‘Lionheart’ in Swahili to his surname. The other ‘guide’, a younger, black lawyer, Marcel Yabili, sort of whitewashes the colonial times, seeking parallels between servants now and colonized Congolese.

Both men express themselves in long monologues and are hard to interrupt – which Guy Woueté tries several times in vain, while listening to Yabili. In the video, you can see his irritation grow.

‘How can you contribute to the decolonial debate if you are not allowed to interrupt?’, Woueté says chuckling, in a telephone conversation from Antwerp, where he now lives, recalling the moment he was filming in Lubumbashi. With the installation, Woueté wanted to show that ‘you cannot enter the colonial past through one door, with one key’, he says. ‘Multiple views are possible. If someone says: there is only one way to fight racism, to fight assimilation, I disagree.’

Woueté cannot work in isolation from society

Woueté cannot work in isolation from society, he says; l’art pour l’art is not for him. This was already clear from the moment he got interested in art in Cameroon.

As a 17 or 18-year-old, he left school after his father died. First, he worked as a mechanic, later he helped his uncle in his residence in Douala. Regularly, he visited the studio of Iya Simon, a sculptor who became a friend, and who raised his interest in art. But in modern art, he found out during self-study, ‘it takes a long time before you come across someone who looks like yourself. Not in surrealism or cubism. It was only when I studied the Cobra-movement, that I discovered Ernest Mancoba (1910-2002), a painter from South Africa. After that, I learned about the artist Thami Mnyele.’

The foundation named after this artist, who was brutally shot in 1985 in Botswana by South African soldiers, invited Woueté in 2006 to visit Europe for the first time. He got the award – a three months stay with accommodation, free visits to museums, use of a fully equipped studio and two bicycles – in 2006. He enjoyed it tremendously, for many different reasons. Most important, he says, was the freedom and the lack of pressure to produce a certain number of art pieces. ‘At other artist residences like in France for example, they kind of expect you to show the world how wonderful their institution is that allows you to work there. There was no need for such a thing at the Thami Mnyele studio in the Netherlands.’

He also enjoyed all the meetings with colleagues and the visits to museums, especially seeing the original painting The Potato Eaters by Van Gogh. ‘This work says a lot about the position of the working class in the Netherlands and is still relevant for the fight for social justice. Much more interesting than Van Gogh’s sunflowers, for example.’

After this first European experience, he studied at the Rijksakademie van beeldende kunsten in Amsterdam 2009-2010. Later, he took a road trip to Calais to do research on immigration in ‘The Jungle’, the camp that was dismantled in October 2016.

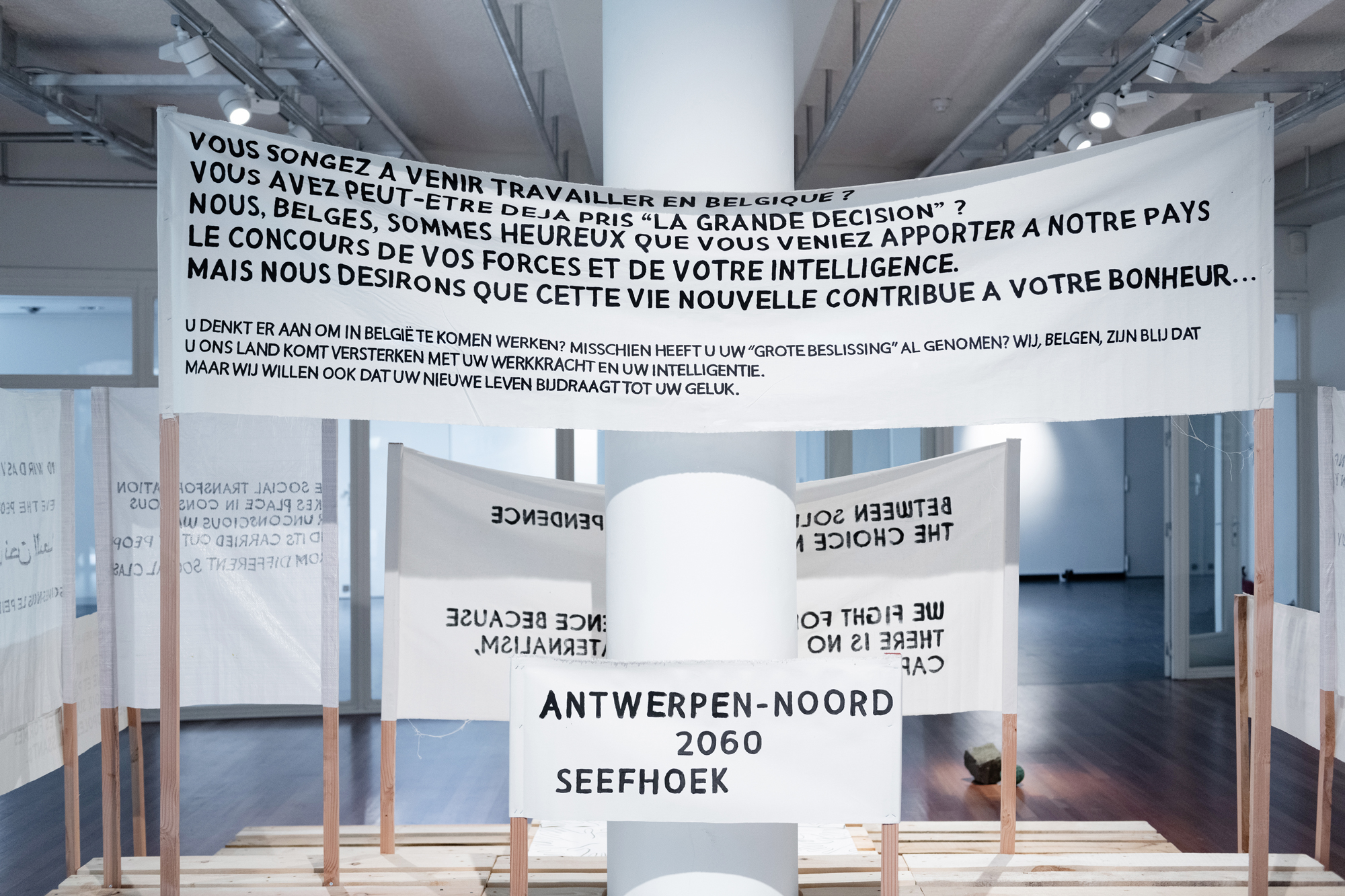

Migration still is an important theme in his work, as is immediately clear from the exhibition Welkom: the first room in de Brakke Grond shows a bundle of protest banners and boards with texts like ‘We, Belgians, are happy that you come to strengthen our nation with your work and intellect’. It is a quote from a brochure the Belgium government distributed in the sixties to motivate migrant workers from Morocco, Tunisia and Algeria, Woueté explains. ‘Migrants come with a rage on their faces to Europe: they want to work here, none of them comes to retire. I’ve seen them work in heavy, stupid jobs, like cleaning oil tanks or containers in the harbour. They don’t complain, but are treated with disrespect, nonetheless. I want to use my position to point that out. There is always something you can do to raise awareness.’

'There is still little diversity in Dutch art institutions.'

In spite of his appreciation for his stay in the Netherlands, he would not like to live there at the moment. ‘Look at the treatment of migrants: in the Netherlands you don’t hear much about it. In Belgium, the social movement is much stronger. And take a look at the art scene and the art institutions in the Netherlands: there is still very little diversity.’

For a migrant, life in Belgium can be better, he says. ‘There is a space here to be different and still belong, whereas in the Netherlands – and I hear this from my friends there – you are never Dutch enough.’

He also did not feel comfortable in the Netherlands because of the individualism. ‘You are together alone’, he summarizes it. That is why he was so happy with the help of the South African artist Moshekwa Langa, a 'Thami Mnyele' alumnus and a board member of its foundation in 2006. Langa picked him up from the airport and helped him around in the art scene and daily life in The Netherlands. ‘Luckily, he was there to explain those things about the Netherlands and to keep me company at important moments.’

Now, with the devastating influence of the corona crisis on daily life, including the arts, Woueté hopes something will change. ‘Hopefully it creates a deeper understanding of togetherness and more solidarity. As a consequence, we might look at the capitalist system in its current form – and realize that something else is possible.’

The exhibition Welkom is open from 3rd of June to the 12th of July in de Brakke Grond.