On June 14, 1985, Thami Mnyele was killed in Gaborone (Botswana). The 36-year-old artist was part of a community of South African political refugees. Eleven others died with Mnyele, including children. The attack by the South African army was carried out under the command of General Constand Viljoen. Foreign Minister Pik Botha had given permission for the attack that took place on foreign territory and could have diplomatic repercussions. A witness for the Truth & Reconciliation Commission testified that Botha showed no hesitation. After signing the instruction to kill, he said: “Waar is die brandewyn, manne? Kom, ons drink!" (Where is the brandy, folks? Come, let’s drink!)

A day after the attack, the brain behind the operation, Colonel Craig Williamson, appeared in a news broadcast on South African state television. He showed one of Mnyele's drawings as proof of “terrorist activity.” Mnyele had been part of an artists' collective that left behind an impressive collection of political prints. Even before his flight into exile, in his birthplace Alexandra (Johannesburg), Mnyele showed a great love for the arts. Encouraged by his parents – his father a Methodist priest, his mother a domestic worker – Mnyele attended various art courses. He would also set up a theatre group in Gaborone.

In 1985, Mnyele participated in the Amsterdam conference "The Doors of Culture Shall be Opened," organized by the Anti-Apartheid Movement in collaboration with debate centre De Balie. Mnyele stayed in Amsterdam at the residence of Bert Holvast and Moira Whyte who were active supporters of the Dutch Anti-Apartheid Movement (AAM). In 1990, 30 years ago, they took the initiative to name an artist residence for (South) African artists that they had founded after Thami Mnyele.

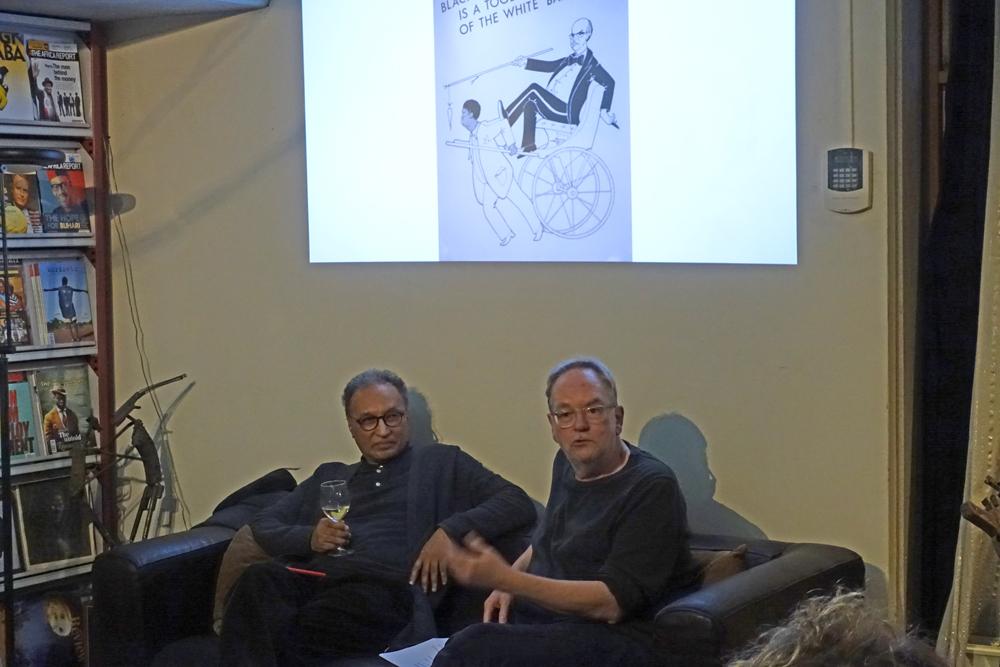

During a moving Studio ZAM event, organized in collaboration with the Thami Mnyele Foundation, memories of the artist were brought together on January 17, 2020. Memories about the artist-in-resistance and the artist-in-residence.

Nearly 50 people joined this Friday afternoon in a crowded studio. The internationally renowned artist, curator, and writer Gavin Jantjes came over for the event from London. In the eighties, he met Mnyele several times, both in Gaborone and in London. Whyte and Holvast also attended the event, as well as Conny Braam, a writer and former president of the Dutch AAM, who met the artist in Gaborone in 1982 at the first conference where debates were held about the role of culture in a future, free South Africa. Annemarie de Wildt also came to the studio with an album of photos showing Mnyele's mother, taken in 2004, shortly before her son's funeral in South Africa, and images of the funeral itself. Sean Fitzpatrick, who left South Africa after his friendship with a black man caught the attention of the police, was also in attendance. Shortly after his departure, he heard from South African activists in London about the South African Defence Force’s attack on Mnyele. Also in the audience were young artists, students, new activists and children of former activists curious about the story behind the name of the artist residency in the Amsterdam Kinkerbuurt.

In a conversation with ZAM editor-in-chief Bart Luirink, Jantjes remembers his first meeting with Mnyele. “I was invited to come to Gaborone and talk about the role of the artist in society. Thami was waiting for me at the airport and showed me the way to the toilet. While I was urinating, I saw someone watching me through a mirror. ‘That is the South African police,’ Thami explained. ‘They follow me everywhere.’ When we got into the car, Thami called to the spy and his colleague: ‘Please follow me!’ Are you not terrified?, I asked in the car. But Thami laughed it away. He knew no fear.” In 1978, wading through a crocodile-filled river, the artist had crossed the border between South Africa and Botswana.

Jantjes had long conversations with the artist and looked at his portfolio. As a curator, who over the years has put together exhibitions with the works of Marlene Dumas, Nicholas Hlobo and Yinka Shonibare, contributing to an impressive career, he is known for his eye for artistic talent. "Thami unquestionably had that," said Jantjes. “There was a lot of politically tinted work – posters, flyers, sets of theatre pieces. But I also saw other work, more non-figurative, in which you recognized the contours of his own signature.” But Mnyele also had many other qualities. Jantjes: "He was a visionary, he had a great organizational talent and was an outstanding fundraiser."

Mnyele's involvement in underground work at the ANC – he underwent military training at a base in Angola – was also discussed. In 1970, Jantjes, born in Cape Town’s famous District Six area, a multicultural neighborhood that was completely bulldozed under apartheid, moved to Hamburg after frequent police visits. “Twenty thousand South African exiles lived in London. I just wanted to get to know other people." In West Germany he was strongly influenced by the work of theatre maker Bertold Brecht – "even though you had to travel east to see his plays on stage. Jantjes: "Brecht taught me: You need to take your imagination, you apply it and go into institutions to change them. Thami and I differed on this. He saw no other way out than to fight apartheid with armed action."

How did Jantjes hear of Mnyele's death in June 1985? “A friend from Zimbabwe told me. I was devastated, in shock. And I was under the impression that his comrade Wally Serote (a poet and ANC stalward) was also killed. But a little later at an exhibtion in London, I heard somebody shouting at me and I knew it was Wally. I turned around and I said: "My God, I thought you were dead. It turned out that he wasn't in Gaborone at the time. The Kenyan writer Ngugi wa T’hiongo had asked Wally to present a paper at a conference in Nairobi. If he would not have been invited ... "

Mnyele’s was not the only name mentioned at the Studio ZAM gathering. Conny Braam remembers Jeanet, Marius and Katryn Schoon being present at the 1982 conference in Gaborone. Four years later, in Angola, Jeanet and Katryn were blown apart by a letter bomb sent by Williamson. Braam also met with Dulcie September who was killed in Paris in 1988. Jantjes recalls Ruth First, another victim of a letter bomb, killed in Maputo by Apartheid death squads, and Albie Sachs, who lost an arm and eyesight as a result of a carbomb in Harare.

Mnyele came to life in a short extract from a documentary at the 1982 conference in Gaborone. In a conversation with South African artists David Koloane and Gordon Metz, Mnyele emphasizes the artist's responsibility in the fight for justice. After that screening, a portrait of Mnyele, painted by Clifford Charles, one of the first residents at the Mnyele Foundation’s studio, was revealed. It will be on view at the ZAM Studio for the coming months.

Finally, the residency's founder Bert Holvast, paid homage to the many people who have kept the studio “alive and kickin’” for so many years. “Some cultural institutions have a Wall of Fame with names of people who donate to them. The Thami Mnyele Foundation always had the financial support of the Amsterdam City Council and othes but never had big money. As the current chairperson, Pauline Burmann, recalled at the event, it is predominantly volunteers who keeping the foundation going. What’s helpful is the recognition by bigger institutions like the Stedelijk, Rijks and Amsterdam Museum, the Prince Claus Fund and others. Holvast: “But we have our imaginary Wall of Fame. It contains the names of former Amsterdam mayor Ed van Thijn who praised the residence as a 'gift to Amsterdam', former treasurer (and Minister) Irene Vorrink, journalist Ischa Meyer, Board member Jules van de Vijver and artist Marlene Dumas who have all supported our work.” Because of the 30st anniversary, Holvast handed flowers to Pauline Burmann, driving force behind the residence for many years, and the latest addition to Holvast's imaginary wall.

About the Thami Mnyele Foundation.

Read The Artist Who Was Not Allowed To Be.