… In that Empire, the Art of Cartography attained such Perfection that the map of a single Province occupied the entirety of a City, and the map of the Empire, the entirety of a Province. In time, those Unconscionable Maps no longer satisfied, and the Cartographers Guilds struck a Map of the Empire whose size was that of the Empire, and which coincided point for point with it. The following Generations, who were not so fond of the Study of Cartography as their Forebears had been, saw that that vast Map was Useless, and not without some Pitilessness was it, that they delivered it up to the Inclemencies of Sun and Winters. In the Deserts of the West, still today, there are Tattered Ruins of that Map, inhabited by Animals and Beggars; in all the Land there is no other Relic of the Disciplines of Geography.

– Suarez Miranda, Viajes devarones prudentes, Libro IV, Cap. XLV, Lerida, 1658

Jorge Luis Borges, "On Exactitude in Science" in Collected Fictions, trans. by Andrew Hurley.

Ng'ambo Atlas is a large book, as atlases often are, to reproduce their maps at a legible scale. Not quite as large as the territory it attempts to map, as is the case with the Map of the Empire in Borges's short story quoted above. Not physically anyway, but perhaps so in the scale of its stated ambition: "... a survey of [Ng'ambo's] built environment (as a key element of the tangible heritage) and mapping of the immaterial culture (as part of the intangible heritage) ..." (176).

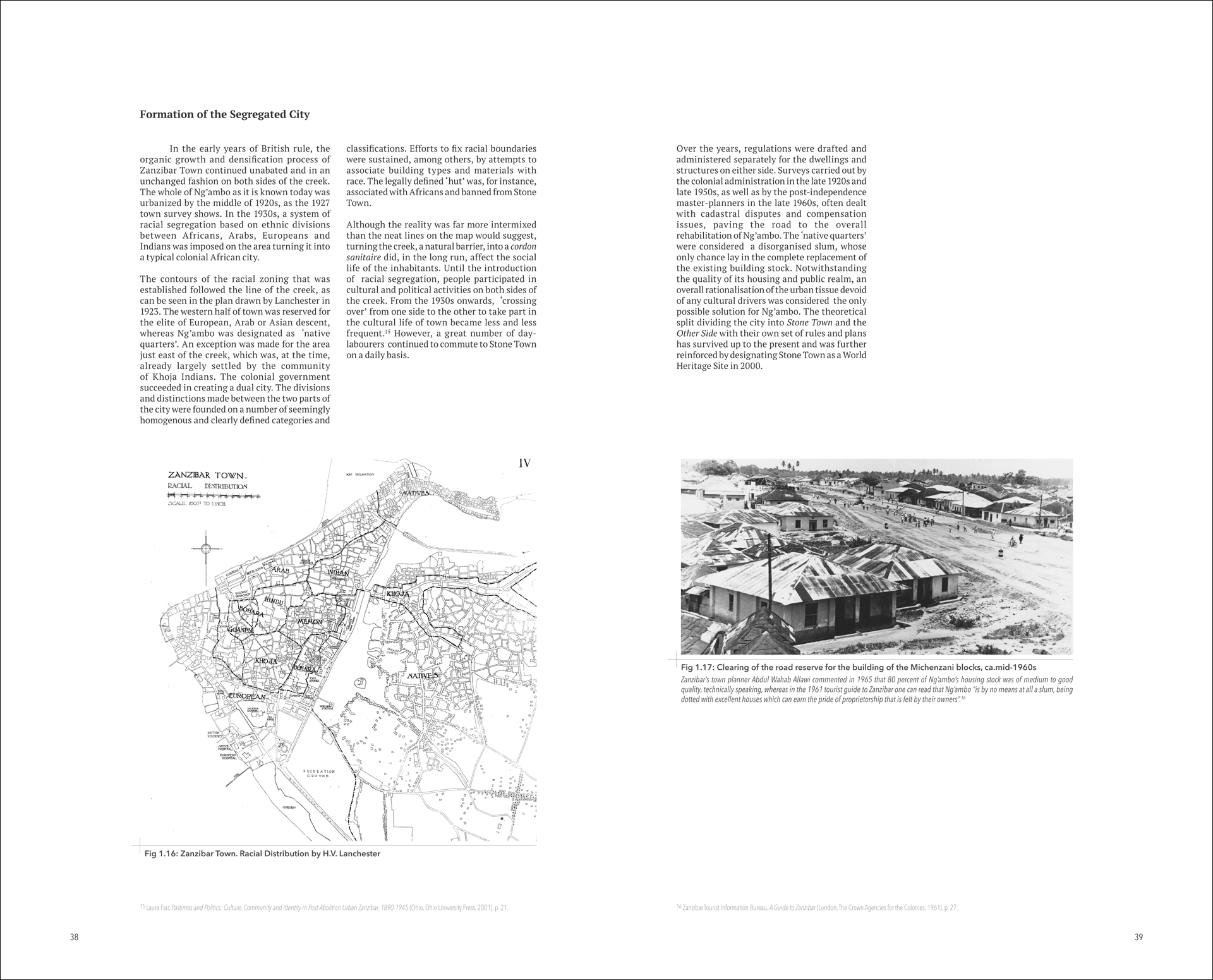

At the outset, Ng'ambo Atlas should be commended on two points. The first is the book's focus on Ng'ambo, the "other side" of Stone Town. By taking this focus, the atlas works to correct the colonial separation of Stone Town from Ng'ambo, implemented along racial lines when Zanzibar was a British protectorate. Stone Town was seen to house the rich merchants, predominantly of European, Arab and Asian decent, while Ng'ambo, physically separated by a tidal canal (part of H. V. Lanchester's 1923 Zanzibar Town "Improvement" Scheme), was home to the "native" population. The intention behind the Ng'ambo Atlas is to address this historical divide by demonstrating how Ng'ambo has played a crucial role in the development of Zanzibar's capital city. An interesting point for reflection is the fact that UNESCO's declaration of Stone Town as a world heritage site in 2000 served to reinforce the perception of Ng'ambo as less important than its neighbouring suburb, highlighting how global agendas often gloss over local realities, imposing a new kind of prejudice.

The second point to be commended, which is also the books greatest weakness, is the attempt to survey the "immaterial" landscape of Ng'ambo. As acknowledged by the Editors in the introduction: 'It is difficult, if not impossible, to compress the diversity, dynamic and complexity of the place onto the pages of an atlas'. Here they allude to the impossibility of recording in any objective manner, regardless of the methodology and tools used – in this case oral histories and field recordings – the intangible moment of place making. In nonetheless pursuing this objective, the Editors are following another UNESCO recommendation, the Historic Urban Landscape, or HUL approach, adopted in 2011, which places equal importance on the 'intangible' components of an urban environment when considering its preservation.

Chapter two: Cultural Landscape of Ng'ambo is given over to this purpose. On a closer reading though, it is only one section, Toponymy (pp. 110-15), which amounts to five of the 192 pages that make up the book, that touches on ‘immaterial’ heritage, while the rest resorts to the geographer's tried and tested surveying techniques, identifying and naming – in short, mapping – physical locations in the urban environment. It is in the place names found in Ng'ambo's neighbourhoods that facts, figures and locations – all the stuff out of which the traditional atlas is made – are replaced by myth, by story-telling, by conflicting 'truths' and uncertain origins. For example, Maskani, popular meeting places for men in contemporary Ng'ambo's neighbourhoods, have names like More Trick Maskan, Cowboy Sound System Maskan and Sao Paulo Madrid Maskan. Or looking further back, to the trees, equally important as the buildings to Ng'ambo's neighborhoods, we find Mwembe Kisonge, translated from Swahili as 'the mango tree where they danced', or equally poignant, Mwembeshauri, the "advice mango tree."

As the author of this section on toponymy states: "The more contemporary names and nicknames given to places for social gatherings are beyond the scope of this study, but it does not make them any less relevant for understanding the city's cultural landscape." Enticed by the list of names this section presents, one can't help but feel that a different kind of book, one in which this naming activity is not beyond its scope, but precisely its subject matter, would provide a better insight than the atlas into Ng'ambo's heritage, physical or otherwise. Better still would be no book at all, but rather getting advice under the mango tree itself. Participating, in other words, in tacit knowledge, the moment of place making as it happens, as opposed to recording and documenting this activity.

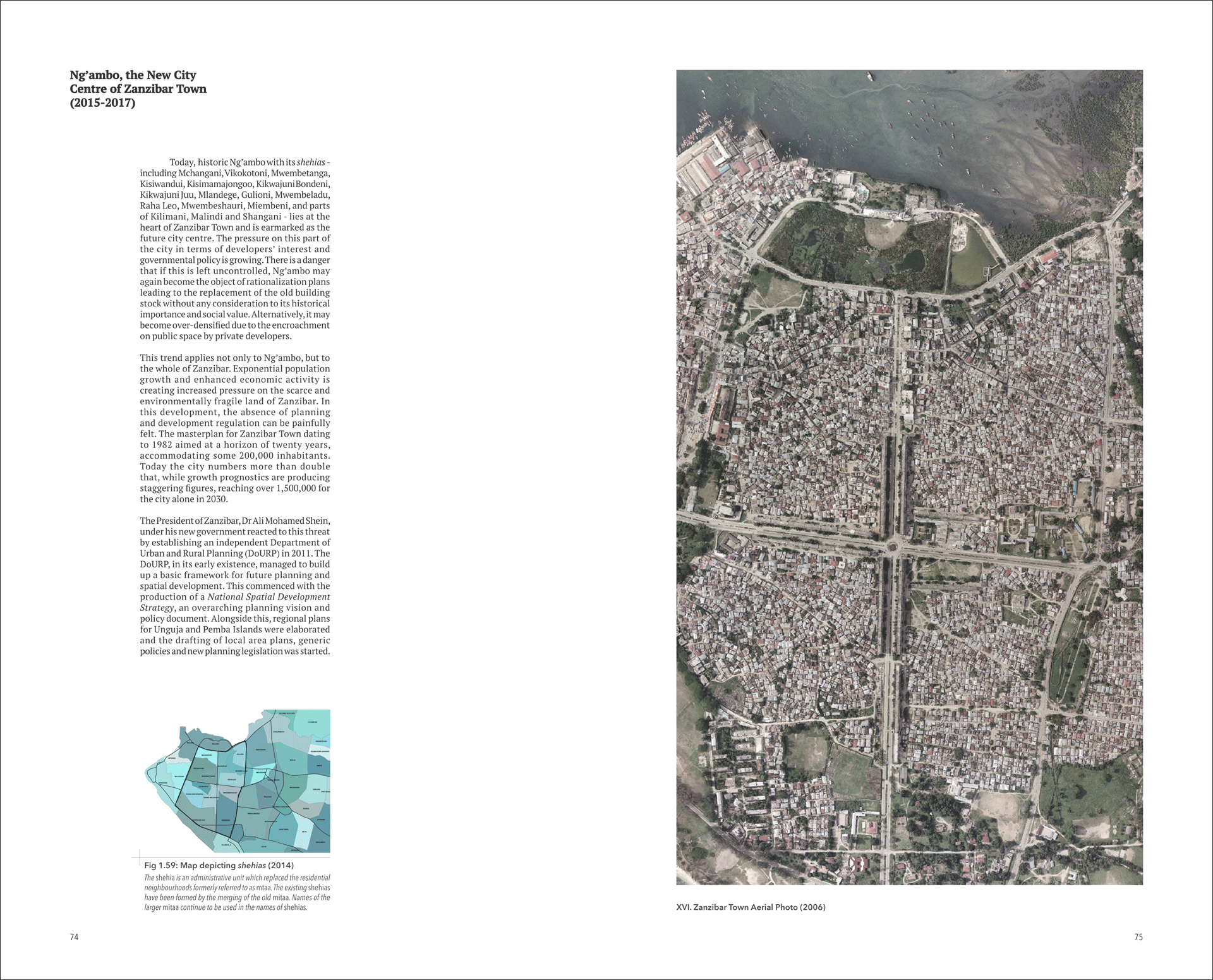

Chapter one of the atlas gives an historical outline of Ng'ambo's development, from Portuguese rule in the sixteenth century, through British colonialism, to the Zanzibar revolution, to contemporary times and the New City Centre of Zanzibar Town. There are many well-reproduced, legible maps that illustrate these developments, a fairly consistent flow of photographs (black and white and colour) depicting notable buildings and a scattering of plans and elevations. The writing is matter of fact, but to its credit, reflective of the shortcomings and difficulties of the book's task. Occasional first person accounts, culled from oral histories, make it into the text, but these have the reverse effect of highlighting the absence of a diversity of voices.

For an atlas, there is a considerable amount of terra incognita; that is generous amounts of white space and often whole blank pages throughout the book. This raises questions about the production value and intended audience, probably not your average person on Ng'ambo's streets. Stone Town's perhaps, but more likely a Dutch and European audience with a specialist interest and deeper pockets. This raises further questions about both the intentions behind and the output of cultural collaborations between "developed" and "developing" countries. The book is the concluding output of the broader Ng'ambo Tuitakayo project, a collaboration between the Department of Urban and Rural Planning in Zanzibar, African Architecture Matters in Leiden and the City of Amsterdam. While chapter four deals with 'Project History and Context', the focus is more on process, while the motive for the Dutch interest in the future of Zanzibar Town's urban planning and the intended outputs of the project are never explicitly laid out or reflected on in the book.

While Amsterdam and Zanzibar have a common status as UNESCO world heritage sites, providing a basis for information sharing as both cities face future heritage challenges, this is as far as the book goes towards explaining the motives for the collaboration. Questions of contemporary cultural imperialism should not be posed lightly and it would be going an exaggeration to pin this label onto Ng’ambo Atlas. Still, when considering how such projects are financed and whose interests are served by their outcomes, questions must be asked about format and the epistemologies they represent and inform. The atlas brings with it all the codes of empire making that were integral to the colonial project, which is not to claim that colonised populations did not develop and use maps themselves. At the risk of stating the obvious, the point is that the coloniser’s atlas always originated from the outsider's perspective, describing in apparently objective, scientific terms what was essentially a subjective view with a specific agenda. One would hope, as is the case with the "following Generations" in Borges’s short story, that the difficulties of the atlas and the territories it claims to represent, and the type of knowledge it embodies, would be well understood by now.