How the killing of a Cameroonian journalist silenced investigations into plunder by an internationally-connected elite, eliminated a rival for the succession of an ageing president, and sidelined a tax director.

A dossier full of bank slips, payment instructions, and tables of sums amounting to tens of millions of dollars, printed by government printers and handed to a journalist, became the downfall of an upstart candidate who had been positioned as a possible successor to ageing autocrat president Paul Biya (90) in the central African country of Cameroon.

It also silenced investigations into illicit financial outflows and killed a journalist.

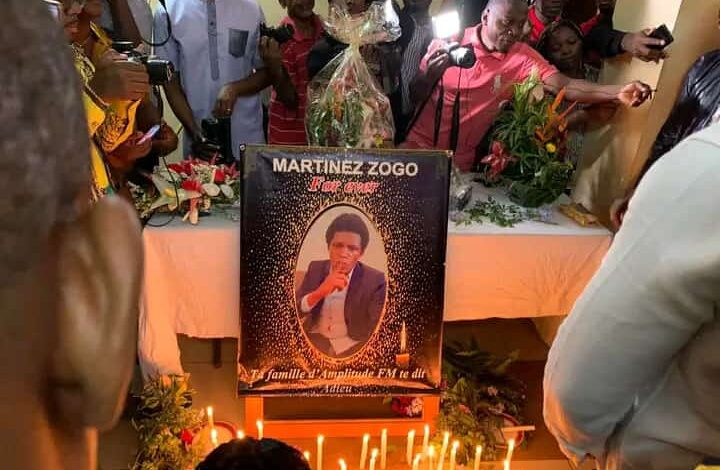

This is the shocking finding of an “Arizona Project” investigation into the gruesome torture and murder of journalist Martinez Zogo in January this year. The project conducted both inside and outside Cameroon by ZAM, in partnership with the Network of African Investigative Reporters and Editors (NAIRE) as well as a number of international partners, found that the story that killed Martinez Zogo was a trap both for a rival in currently raging palace wars, and for the journalist himself.

Vultures circling over the expected-to-be-dead-soon autocrat President Paul Biya sacrificed a competitor and covered up their own plunder in one fell swoop.

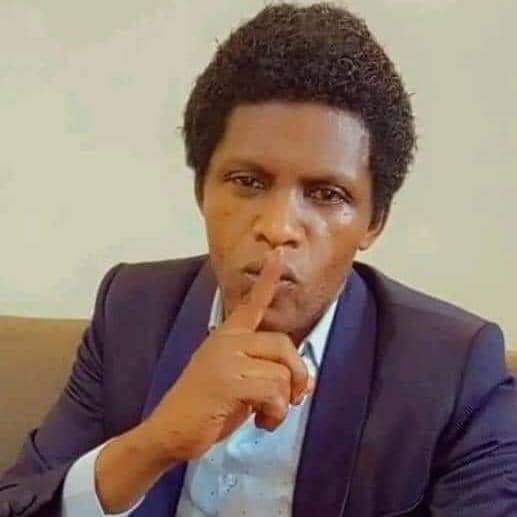

When radio journalist Martinez Zogo’s severely mutilated body was found on the side of a street in a Yaoundé, Cameroon suburb on 22 January 2023, Cameroonian police immediately went out to arrest the alleged mastermind of the killing. That was local media tycoon Amougou Belinga, owner of the influential television channel Vision4 TV and newspaper L’Anecdote. Belinga was known as much for his powerful political connections and street-fighting style as for his ambition to become the next President of Cameroon after the soon-expected death of autocrat leader Paul Biya, now 90.

Read more: The life and trials of a media tycoon

These ambitions were well known. The media entrepreneur, who had once come from lowly beginnings, had enjoyed a recent, astronomical rise into politics. Many residents of the capital had noted Belinga’s wife comparing herself to current first lady Chantal Biya, known for her big red wigs. “At least my hair is natural,” Mrs Belinga had said in public, at a donation ceremony at an orphanage, only weeks earlier.

The media tycoon had presidential ambitions

According to the police, and echoed by dozens of physical and online media in Cameroon, Belinga had Zogo, whose real name was Arsène Salomon Mbani Zogo, killed. Belinga would have been angered by the journalist, who had, in the week before his abduction on 17 January, quite forcefully and repeatedly accused him of large-scale corruption. When Zogo’s tortured remains surfaced five days after his kidnapping, the police did not take long to conclude that this had been Belinga’s revenge.

Listen to an audio clip of Martinez Zogo denouncing Amougou Belinga.

The police also claimed that they had a statement from the leader of the group of killers who was, ironically, a police lieutenant colonel himself. Officer and deputy director of the secret service ‘General Directorate for External Investigations’ (DGRE) Justin Danwe, who was also immediately arrested, had named Belinga as the mastermind.

Arizona

You can kill a journalist, but you cannot kill the story

On 12 April 2023, a team of NAIRE members (David Dembélé from Mali, Selay Kouassi from Ivory Coast, and Bram Posthumus, who is Dutch and lives in Abidjan) land in Yaoundé. Our mission is to conduct a so-called “Arizona Project”. The Arizona Project model dates back to 1976, when, in Arizona, US, journalists from all over that country came together to finish the investigation reporter Don Bolles had been working on when he was murdered by organised criminals. Ever since, the “Arizona” motto has been: You can kill a journalist, but you cannot kill the story.

We are here to ask: what was the story that killed Martinez Zogo? Was it his exposure of corruption involving Amougou Belinga?

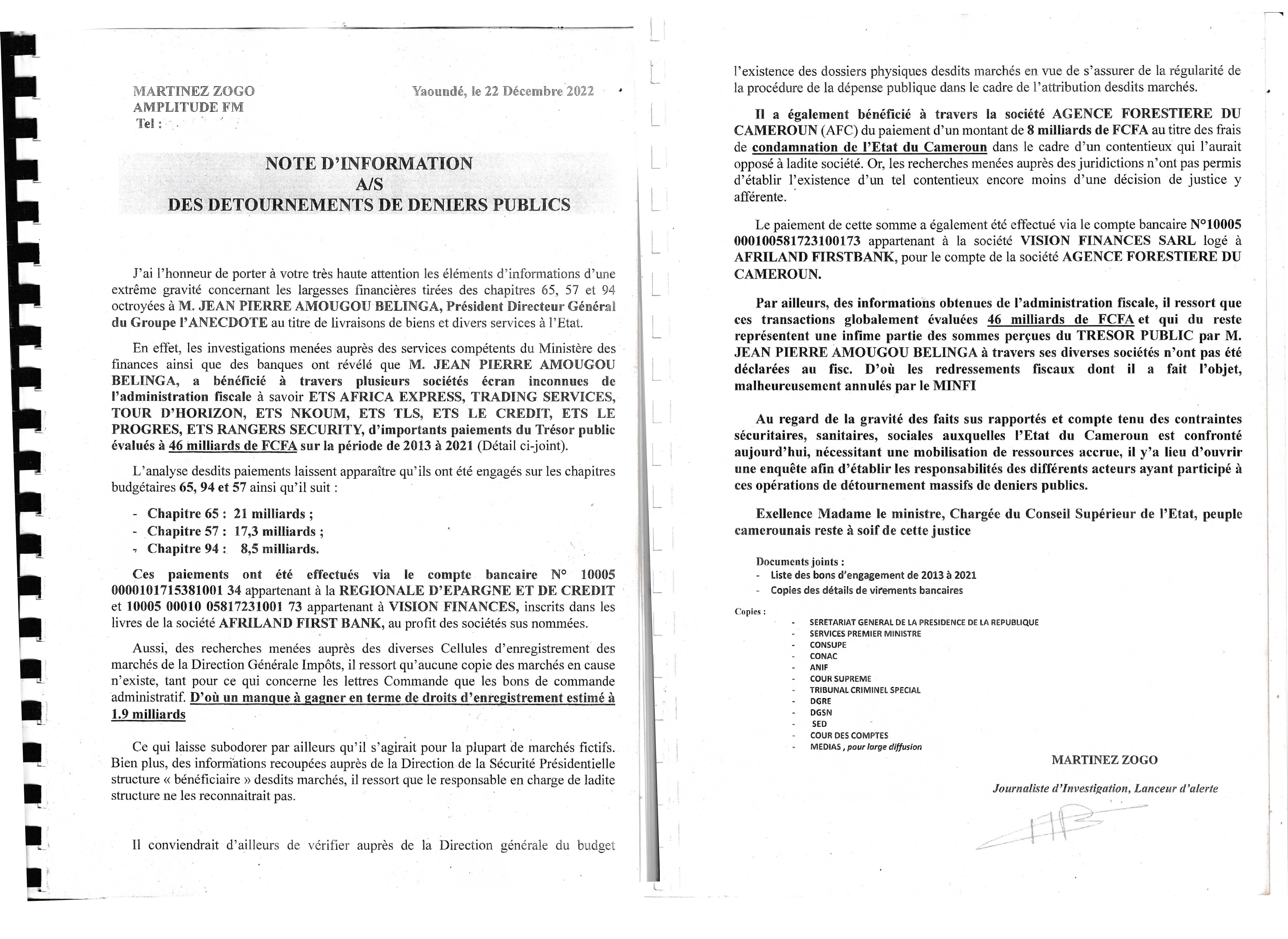

Zogo would certainly have annoyed Belinga, that much is clear. Zogo had repeatedly, on live radio, announced that he had an entire dossier on the man. The radio journalist had gone into detail, listing payments to Belinga from state coffers to the FCFA equivalent of US$ 79 million over the past ten years. “I have the proof!” he had shouted. “I already sent it to the president!” Interestingly, despite his popular broadcasts denouncing corruption, Zogo was known to be a loyal Biya supporter: he had believed the president to be above such shenanigans.

It is possible that the police are right, and Belinga, who has been rumoured to use mercenary men to intimidate and exercise violence against his enemies, had the murder carried out on his orders.

But as our team arrives in Cameroon, we are confronted with a further mystery. The arrest of the alleged murderer seems not to have provided any relief to our fellow journalists, or, for that matter, anyone else in civil society. On the contrary, wherever we go, fear and silence suffocate almost every interaction, every engagement. People – from the two Cameroonian anti-corruption commissions, to lawyers, to parliamentarians, to a good number of colleagues – are not picking up their phones. Or they promise to see us and then don’t show up. Or, in the rare case that they do show up, they are very, very cagey indeed.

Two subjects seem particularly taboo: any and all investigations into any corruption involving anyone else besides Amougou Belinga; and the succession of President Biya.

Palace wars

We soon get the feeling that the presidential succession may be crucial in all this. The whispers are everywhere: Belinga was a rival to other powerful players in the current palace wars, we hear. These players, ministers and high-level civil servants, divided into separate factions, are fighting one another for access to the throne and the state coffers, positioning themselves for the moment when the nonagenarian president who has reigned for 48 years will finally kick the bucket. The arrest of Belinga has removed one important rival.

Powerful players are fighting for access to the throne

The fear is infectious. We hope that this country’s shadowy forces of violence won’t hurt foreigners – but who knows? Two other journalists have been killed here in the few months since the Zogo murder. Our hotel is called the Kremlin, too. (Yes, we are staying in a place named after one of Europe’s most prominent hotbeds of corruption, lies, intrigue, secrecy, backstabbing, double-dealing, and murder, while we investigate the same things just north of the Equator. “The owner is a great fan of Vladimir Putin,” a hotel staff member tells us when we ask about the name.)

Our new home base seems well suited for our interviews with people who mostly talk in vague allusions, usually known as Kremlinology, until we manage to break through and establish trust. When that happens, we find that practically all of our carefully selected, background-checked colleagues (who co-exist with hundreds of propaganda outlets financed by political factions in the country also question the official narrative around the murder of Martinez Zogo.

A journalist’s dream

“There are so many corruption cases,” says a colleague who often reports from Cameroon for French media. “But Zogo talked only about Belinga. Why?” He talks of the dossier “full of proof” Zogo claimed to have in his hands. “Why was there a whole dossier only about Belinga?”

The dossier came from government printers

We had already seen the dossier, sent to us by friendly contacts before we arrived in Cameroon. It was impressive. It had government bank transaction print-outs, Excel spreadsheets of payments from government budget heads to Belinga’s companies, signed payment instructions by senior civil servants. There were payments to Belinga from this and that state budget dating back to 2013, with dates, names, and amounts of money, for his business suits (Gucci and Cardin), security, transport, and even fire extinguishers for his office.

Though the footers of most pages had been deleted, we could still make out that much of this dossier had been printed from PROBMIS, the Information Systems Programme of the Ministry of Finance. It looked like someone with access to the government computer system had meticulously searched for anything relating to payments to Belinga, and printed it out. We had initially been quite chuffed with it. It was a 137 pages thick journalist’s dream.

“But that information was all over Cameroon already,” says the same colleague. “Many of us knew about this.” He is right. Zogo had circulated the entire dossier himself, not only to the presidency but also to all government departments, police, the two anti-corruption commissions, the court, the secret service, and colleagues in the media, on 22 December 2022, over three weeks before the abduction that led to his killing. The allegation that a total of US$ 79 million had been paid to Belinga from state coffers was even older. It had been made by other news outlets too, and the media entrepreneur had already taken one to court for defamation. Plus, by 1 December 2022, the date the dossier was printed, Belinga had long been the target of a tax claim for US$ 50 million over undeclared income.

The tax investigation dated back to at least 2021, and reports about the Cameroon government’s grant funding to Belinga for the acquisition of a Paris, France-based TV channel called Telesud had caused outcries as far back as February 2020. “Telesud has an audience of zero,” a commentator had written at the time. “Is this not just money laundering?”

The others

From 2020 onwards, however, reportage on Belinga more frequently mentioned that these payments, besides buying favourable publicity on Vision4 TV and in L’Anecdote for their presumed facilitators, were also propping up the media man as a contender for the presidency post-Biya. In July 2020, a website calling itself the “Cameroon Intelligence Report” had denounced a “conspiracy to make Belinga president as the figurehead of a government faction”.

Belinga’s alleged best friends in government were finance minister Paul Motaze and justice minister Laurent Esso. According to the police, who investigated claims that Belinga had phoned Esso at the time of the murder, Esso had also allocated state-paid prison guards as private security guards for the businessman’s house. Martinez Zogo had repeated accusations against Esso and Motaze as Belinga’s paymasters during one of his broadcasts.

“They were the faction that was positioning Belinga,” says a colleague who is a senior editor. “Others didn’t like that.” What was extra irritating, the editor adds, was that “besides the issue of the different factions, Belinga was also a vulgar man, not sophisticated at all. He was definitely getting too big for his boots.”

“Belinga was a vulgar man”

“We should look at the others,” agrees another colleague, who is close to corruption investigations in Cameroon. “The others are what nobody talks about.”

He goes and comes back with documents from the tax office.

It turns out there are dozens of others.

The Excel documents retrieved by our colleague list 67 foreign exchange companies, tourist and transport companies, mining companies, hotels, money transfer agencies, financial consulting companies, a consortium in Strasbourg, and one “jeune fille ambitieuse”, a “young and ambitious girl” we find when we google the individuals behind a vehicle and touring company for high-end visitors to Cameroon. The sheets, stamped by Cameroon’s revenue service and covering a four-year period from 2017 to 2021, show large amounts paid from state coffers to these entities in order of value, from the FCFA equivalent of US$ 275 million to much lower sums. The total of about US$ 656 million has been paid by the Cameroonian state to companies in Nigeria, Togo, France, and the US. One has a branch in Equatorial Guinea, one is led by an Italian, one organises tourist trips to the Central African Republic. There is also a line with a name, just one name, of a billionaire businessman, reportedly close to President Biya, with investments in South Africa.

There are quite a few recipients we cannot trace. But many on the list of 67 seem to have one characteristic in common: the ability to channel money out of Cameroon.

#NoComment

— Berthier Ace (@BerthierAce) June 1, 2023

Le Milliardaire Antoine Samba en service à la présidence de la République du Cameroun ancien directeur général du budget du Ministere des Finances !.... A pic.twitter.com/uFKoROFHZy

“These kinds of people (corrupt political leaders and their friends) always like tax havens,” comments South African tax expert Yolisa Pikie, who has investigated the billions of dollars siphoned off by the Indian Gupta brothers during President Zuma’s reign in South Africa. “But you especially need to take your illicit money out when there is political turmoil. You may have kept some of it in bags in your house previously, but now you are not sure what will happen if a rival comes to power.”

The tax investigation into 67 cases of money laundering totalled US$ 656 million

Cameroon’s power players are traditionally famous for keeping enormous wealth in their houses (see tweet above). Were they ramping up channelling their loot abroad from around 2017, when the president turned 85?

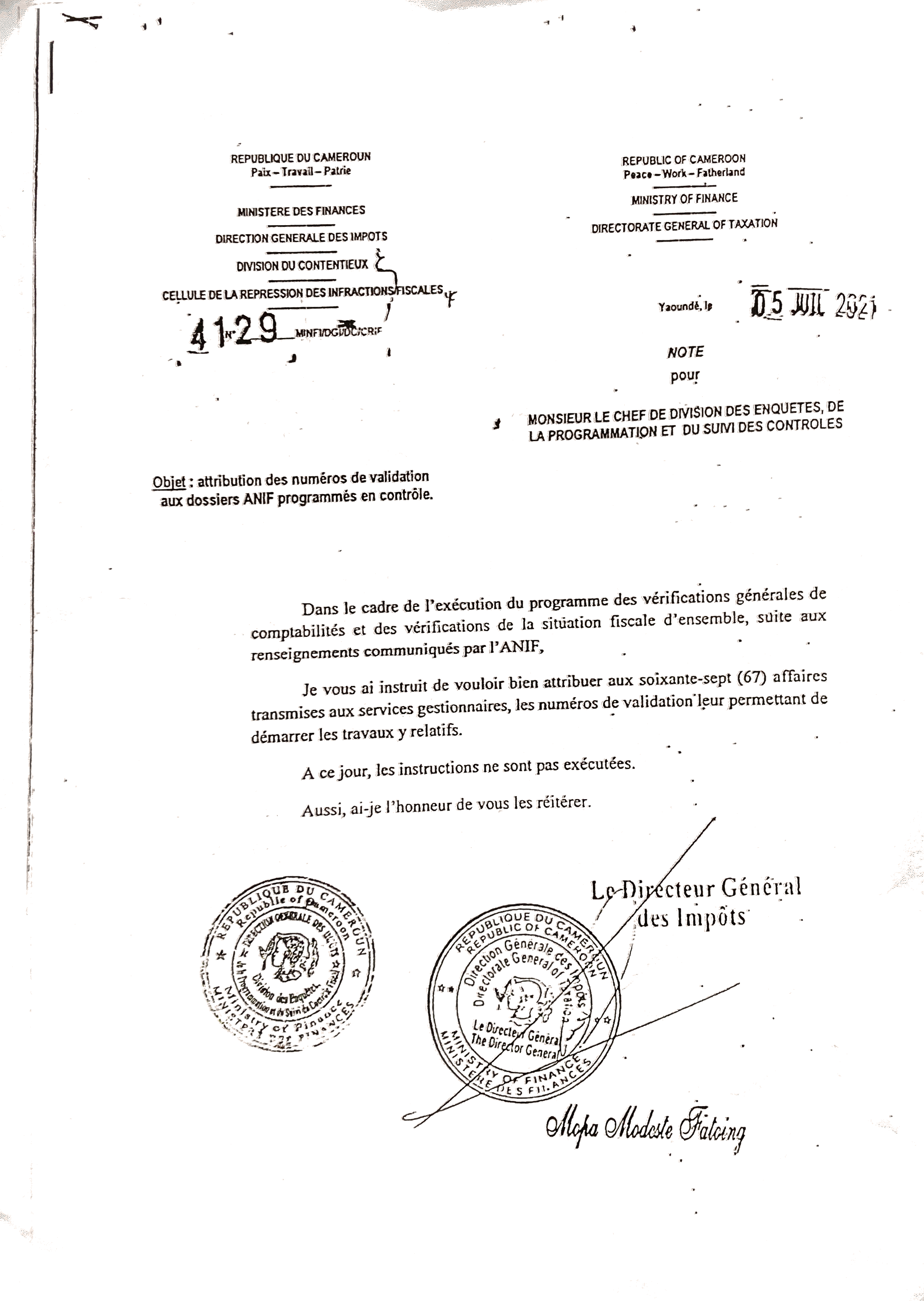

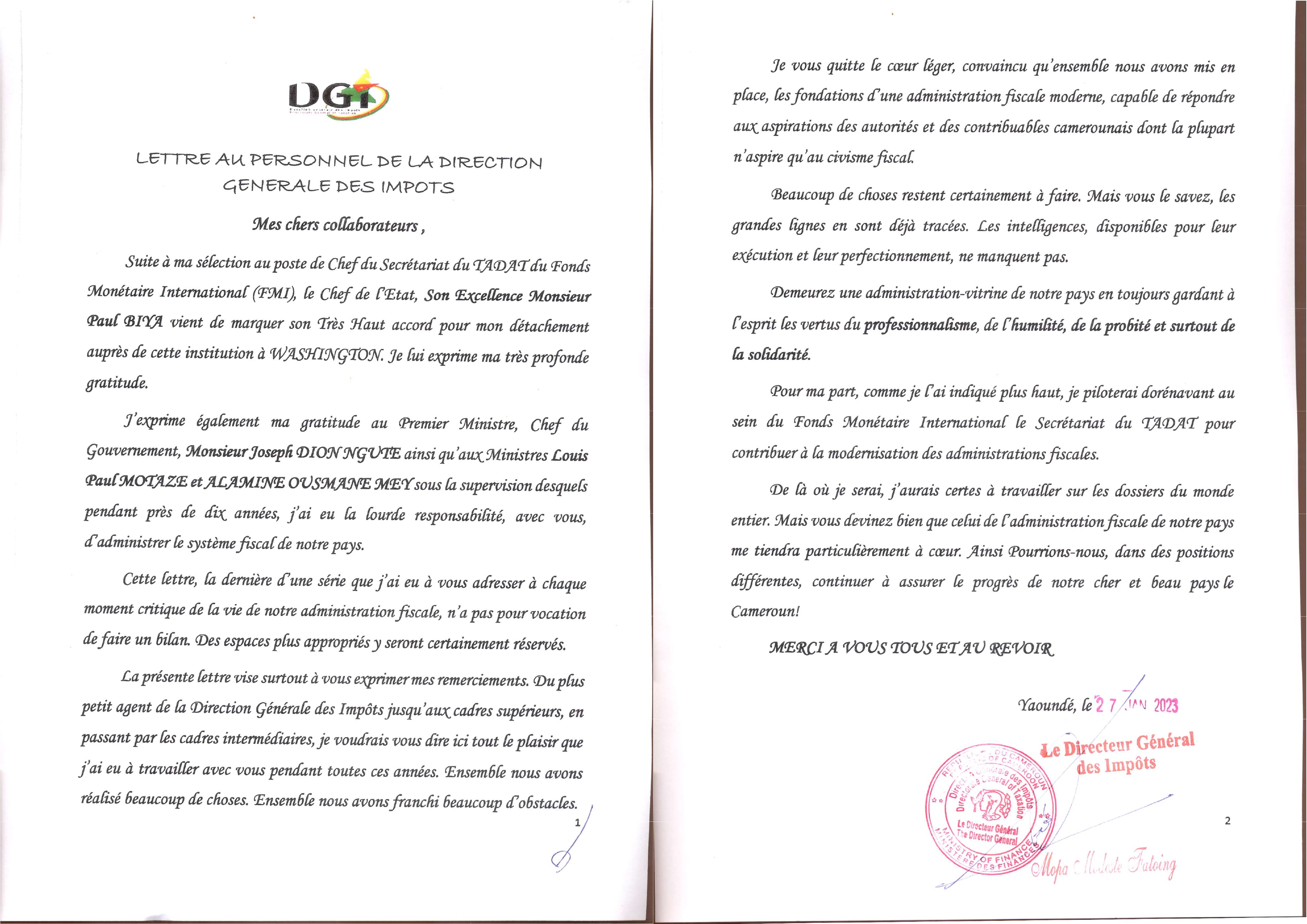

A letter dated 5 July 2021, signed by the then Director-General of Cameroon’s tax agency, Mopa Modeste Fatoing, is stapled to the file. In it, Fatoing reminds his staff to “urgently look at these affairs”. But to date nothing appears to have happened in this investigation.

Letter from former Cameroon tax Director-General Mopa Modeste Fatoing to his investigations division on 5 July 2021.

It reads: “As part of the execution of the programme of general audits of accounts and audits of the overall tax situation, following the information communicated by ANIF*, I have instructed you to kindly attribute validation numbers to the sixty-seven cases transmitted to the services managers, allowing them to start the related work. To date, these instructions have not been followed. I therefore have the honour to reiterate them to you.”

*ANIF (L’Agence Nationale d’Investigation Financière) is an official public financial intelligence service attached to the Ministry of Finance in Cameroon. Its website says that its “mission is to fight against money laundering and the financing of terrorism.” Tax Director-General Fatoing’s letter indicates that the sixty-seven cases he wants to have investigated have been communicated to him from ANIF.

A “context of suspicion”

In contrast, from November 2021, there was again much talk in Cameroon’s media about Amougou Belinga’s benefits. In January 2022, President Biya even ordered a travel ban against the media tycoon, because “he is under investigation for deals with ministers.” In February 2022, the President ordered an audit into all government moneys paid in irregular ways, dating twelve years back, from 2010 up to and including 2021. Practically all that surfaced from this exercise in the media was, once again, a number of reports on moneys received by Belinga.

“Cela arrive dans un contexte de suspicions nées de la circulation, toujours dans les réseaux de documents faisant état de l’utilisation des lignes en question pour le financement des activités de Jean-Pierre Amougou Belinga,” writes the online news site ecomatin.net. “This (audit) happens in a context of suspicions born from the circulation of documents reporting the use of the (budget) lines in question for the financing of the activities of Jean-Pierre Amougou Belinga,” making it seem once again as if Belinga is the only one ever to get such payments. The “budget lines in question”, numbered 57, 65, and 94, are notorious for their secrecy and their suspected use for payments to cronies. They are the specific target of this proclaimed audit.

According to President Biya’s own published assessment, the total of these budget lines since 2010 amounts to close to twelve percent of all state budgets, a whopping 5400 billion FCFA or US$ 8,5 billion. But this staggering figure seems forgotten. According to the Zogo dossier, the total of payments received by Belinga over the past ten years was 46,8 billion FCFA, US$ 79 million, just short of one percent of this total.

But then, in August 2022, a summons for a court hearing was issued to a very significant “other” indeed. The powerful Ferdinand Ngoh Ngoh, the director of the presidency of the 90-year-old Biya, is known to command practically every department in the country’s government “on the highest instructions of the supreme head of state.” He is also said to be a close confidante of Biya’s wife Chantal, she of the giant red wigs and similarly sized ambitions, who already has a whole faction in the palace wars named after her. Ngoh Ngoh, whom she is reported to have brought to government from a lowly UN posting in the USA, is her biggest fan.

Ferdinand Ngoh Ngoh acts “on the highest instruction”

The court in Cameroon – either at the behest of the Belinga faction, or other rivals to Ngoh Ngoh, or out of genuine concern about the allegations of corruption – began investigating reports that Ngoh Ngoh is responsible for the mysterious disappearance of at least US$ 40 million in donor funds meant for COVID relief in 2021. Alerted to this, some media in the country started looking into certain amounts Ngoh Ngoh’s own office received from the budget lines 57, 65, and 94. In October 2022, the court issued an arrest warrant for Ngoh Ngoh.

On the 28th of that month, President Biya ordered the suspension of the warrant, declaring his full confidence in Ngoh Ngoh.

A little over a month later, government printers printed out the raw data about all payments to Amougou Belinga over the past ten years.

The resulting dossier ended up in the hands of Martinez Zogo, who started circulating it around Yaoundé with a covering letter dated 22 December 2022. Weeks later he passionately attacked Belinga on his radio programme on Amplitude FM. He was abducted in front of a police station on 17 January. Five days later he was found murdered, with his tongue twisted and fingers cut off, and other ghastly signs of torture on his body.

Douala, 15 April 2023

A scientific dictatorship

Amid the silence and the fear, only opposition “iron lady” Kah Walla, in her office in Douala, talks to us on the record. Even though she has been arrested for it a couple of times, she still talks, and cautions us. “You may think that the Biya regime is ready to collapse, but there is a whole sophisticated political engineering behind it. It is a scientific dictatorship,” she says. And a violent one: “Biya, old or not, is a master of violence. He practices irrational violence; violence without cause and without logic. Everyone is afraid, since no one knows the limits not to cross.”

Walla is, she says, convinced that in the Zogo case, a “clan within the power wanted to use (the murder) to destroy this other branch. This is what led to all these arrests of high personalities within the circles of power. All the whistleblowers are close to the regime.” And then everything stopped abruptly, she adds. “As if there had been some sort of agreement between the warring branches; as if there was an overnight meeting during which they decided to put the ball down. Like they said to themselves, 'If I fall, you fall too.' And suddenly, overnight, there were no more arrests.”

“Everything stopped abruptly, as if there was some kind of agreement”

Months after the murder, all investigations seem to have disappeared. There is no news on the Belinga case except that he and a number of other alleged killers are in jail and that the trial drags on; nor about the audit into the government budget lines, nor about the tax investigation into the 67 affairs that funnelled so much state money out of Cameroon. The tax director who had pushed for this is gone, too: by declaration of President Biya, Mopa Modeste Fatoing was sent to take up a position at the International Monetary Fund in Washington on 26 January 2023, four days after Martinez Zogo’s body had been found.

Belinga’s government friends, ministers Louis Paul Motaze and Laurent Esso, are reportedly “very quiet now” as well. “They almost arrested Esso too,” reminisces the senior editor colleague, grinning. Very few government ministers are particularly liked in Cameroon.

The second murder

“Your own camp can kill you,” Ola Bebe had said on TV before he was shot

Meanwhile, Kah Walla and her team continue. They are now demanding investigations into a lesser-known murder of a journalist, a friend of Martinez Zogo called Jean-Jacques Ola Bebe, who was found dead with bullet wounds in his face on 3 February 2023, barely two weeks after the Zogo murder. No suspects have been arrested in this case, but – just like Zogo – Ola Bebe had made a public accusation just before his death. Only he had defended Amougou Belinga, saying that in his view, Belinga had nothing to do with it. He had then also told the presenter on private broadcaster Mo’o TV’s daily show Boîte Noire that journalists should be impartial because even “your own camps won’t guarantee your survival.” He had gone on to say that “you get used and afterwards, there is no other win for them, on the contrary, now you are an embarrassing witness (…); at some point you might tell people that it was so-and-so who gave you these documents. And voilà.”

He was found shot the next morning.

Note 1: Football-loving Cameroonians also remember how the African Cup of Nations in 2021 had to be cancelled because large payments, made under Ngoh Ngohs authorisation to a number of US-based companies that he had personally brought in, did not result in the construction of the promised soccer stadiums. Most of the promised ones have not been completed up to today.

Cameroon

Cameroon is a Central African country that had a GDP of US$ 45 billion in 2021. Of its 27 million inhabitants, 55% live in poverty and 38 % in severe poverty. It received a total of US$ 651 million in donor aid in 2021, a similar amount to the illicit financial flows from state coffers to elite-connected individuals and foreign entities which were set to be investigated by its tax authorities over the period 2017-2021.

The ZAM and NAIRE Arizona Project

The Arizona Project model dates back to 1976, when Arizona Republic reporter Don Bolles, who had been working on stories about land fraud and the Italian-American mafia in Arizona, was blown up in an explosion caused by TNT that had been placed under his car. In response to the murder, Investigative Reporters and Editors (IRE) in the US put together a team of 30 reporters who gathered in Phoenix to finish Bolles’s story. It was the first large-scale collaborative investigative journalism project in history.

After the murder of Martinez Zogo, the Network of African Investigative Reporters and Editors (NAIRE) initiated a discussion with ZAM on the possibilities of carrying out an Arizona Project in Cameroon in order to assist colleagues under siege in that country and retrieve important information. ZAM agreed to use its office as a base for the coordination.

The decision to send colleagues into Cameroon was not taken lightly. It would be risky because of the danger of violence, detention, and torture for which Cameroonian security forces are known. However, NAIRE found members willing to go regardless. They were Selay Kouassi from Ivory Coast, David Dembélé from Mali, and Bram Posthumus, also based in Ivory Coast. They were to work in close contact with Cameroon-based colleagues, who had access to information but could not be exposed for their safety. These colleagues, as much as ZAM and NAIRE would like to credit them in full, cannot be named for the same reason.

Investigations editor Evelyn Groenink worked full-time in the ZAM back office to coordinate the project, serve as liaison, and edit the results.

When the team discovered that illicit financial flows from Cameroon to foreign countries were a crucial factor in the murder of Martinez Zogo, international partners in the Global Investigative Journalism Network (www.gijn.org) were also ready to help. These were:

• The Investigative Reporting Project Italy, in particular reporter Edoardo Anziano, who dived into the case on the Italian side.

• Premium Times reporter Kabiru Yusuf, who, in spite of the investigative publication’s heavy workload, was made available by his editors to work on the Nigerian and USA fronts of the story.

• Diario Rombe (Equatorial Guinea/Spain), which investigated a money transfer link between Cameroon and Equatorial Guinea.

• Pierre-Claver Kuvo, editor of De Cive in Togo and coordinator of the Togolese Consortium of Investigative Journalists "Togo Reporting Post", who focused on the links to Togo and Benin.ZAM and NAIRE extend their greatest thanks to these colleagues, who worked with African investigative journalists in solidarity.

The project also owes thanks to the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), which provided crucial and much-needed advice.

Read all the investigative articles in this series:

Cameroon | 67 suspicious transactions

Cameroon | The life and trials of a media tycoon