In an act of defiance, Nigerians decided not to drive on the left side any longer. British colonialism was history.

Nigeria could be seen as an African incarnation of the United States: fervently religious, naively optimistic, highly individualistic and holding a deep disdain for government. For good or for worse, this has earned them the label ‘The Americans of Africa’. After independence, Nigeria chose to drive on the right hand side of the road. This was a defiant step in cutting symbolic ties with the former colonizer, in stark contrast to Britain’s former East African colonies who remained driving on the left and where echoes of Great Britain still resonate.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, author of Americanah, argues that the British presence in Nigeria was minimal during the colonial period. The climate was too harsh to recreate ‘England’, as opposed to the Highlands of Kenya and Uganda, which because of the moderate climate attracted an influx of white British settlers. In her opinion, due to the insignificant presence of the British, the Nigerian mind was never colonised. As a result, Nigerians celebrate strong identities, and are brash and self-assured without a trace of submissiveness. Europeans, as well as fellow Africans, often construe this self-confident demeanour as aggressiveness.

I arrived in Lagos in the wake of some of the worst atrocities perpetrated by Boko Haram. Prior to my departure, Western newspapers had increased coverage of the terrorist group. The reporting on the 200 abducted schoolgirls had gained significant traction, albeit retroactively. I expected the terrorist threat to be prominent in the everyday discourse of Lagosians. This was not the case (although, when prompted, everyone had an opinion). The customary reason given was that the conflict didn’t yet resonate in Lagos, due to the geographical distance. The North is often perceived as a different country – not that unusual, taking into account that the British unification of the Islamic north and the Christian south was as recent as 1914.

A more reflective insight was that the ongoing tensions in the North only grabbed the West’s attention after the founding of Boko Haram in 2002 and its affiliation with Al-Qaeda some years later. Only then did the Western media have a label that it could identify with. Nigerians had been living with troubles in the North for decades. Terrorist threats have not deterred the flow of returnees. The need to contribute to a society in which you have a degree of ownership seems to be the prevailing emotion behind the return of the Nigerians I spoke to. Abulrazaq Awofeso (34), a successful artist who after 13 years in Johannesburg returned to Lagos, summed it up best: “Crippling corruption, terrorism, inequality, corroding infrastructure are all everyday realities, yet life is unpredictable and exciting in Lagos. It’s like stepping onto a fast train that can’t be stopped and not knowing the destination.” The question remains, however: Does the average Nigerian want to get on a runaway train, and even if he does, are there enough seats?

The inequality in Nigeria is blatant, bordering on the obscene. Private helicopters crisscross the sky far above the gridlocked city where fifty percent live on $2 a day. Average citizens trapped in never-ending traffic jams are pushed aside by convoys of SUVs with sirens and flashing lights. In any other country, such convoys would indicate government officials dealing with tight schedules. Not in Nigeria. Here, they are made up of wealthy private citizens on their way to their next business deal or social gathering. The economic discrepancies in Nigeria are vast.

How can you sit in your $ 200 000 Bentley while the street hawker trying to sell you DVDs lives on a dollar a day? Such questions are unavoidable, but they presume and even demand a superior morality from Africans as if, in the light of economic fortune, Africans should demonstrate immediate solidarity towards their less fortunate citizens. I asked myself: How self-evident is solidarity towards the disenfranchised in European society?

Does Europe have the right to condemn the sometimes-harsh reality of economic growth within the African context? Europe has vigorously embraced the free market economy, proclaiming it to be instrumental in the fight against poverty in Africa. Is it then justified to condemn new burgeoning African economies, even when social inequality is very much in the forefront?

This is an excerpt of African Tabloid, published by ZAM late last year. More information here.

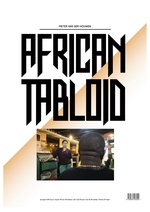

Photo by Pieter van der Houwen, Abdulrazaq Awofeso at home in Lagos after living in South Africa for 13 years.